For a generation, James Benning has been exploring American places and American history in films that have challenged our increasingly short attention spans and are a major contribution to what has come to be called “slow cinema.” Those who have followed Benning’s long career (his filmography begins in 1971) will remember 13 Lakes (2004), which was admitted to the Library of Congress’s National Film Registry in 2014, and TEN SKIES (2004), both of which—like EIGHT BRIDGES—are composed of a series of 10-minute shots, each divided from the next by a moment of darkness (in the 2004 films, 10 seconds; in EIGHT BRIDGES, 5 seconds).

After RR (2007), a series of extended shots of railroad trains passing through the landscape (and the film frame), one train per shot, Benning moved from 16mm to digital, at least in part because the prints he had been making were often scratched during projection. The change to digital also offered expanded options for long takes. Ruhr (2009), which surveys the Ruhr valley in Germany, concludes with an hour-long shot of a cooling tower for coke (a form of coal, condensed by heat, necessary for the production of steel). And BNSF (2013), a “single-shot” film that records one scene in the California desert through which many trains pass every day, lasts 3 hours and 20 minutes (it was recorded on a series of SxS memory cards, each of which can record for nearly an hour, so there is no visible interruption between the memory cards).

Though Benning has made many films, most all of them rigorously organized, the experience of EIGHT BRIDGES not only evokes his long-take serial films of the early 2000s, but also builds on them.

My first experience of seeing EIGHT BRIDGES on a big screen with good sound felt simultaneously nostalgic and novel—and not only because Benning’s digital image is in a wider aspect ratio than his earlier analog films. Each extended 10-minute meditation on a new bridge is visually and sonically organized in a particular way. The Golden Gate Bridge shot, which begins the film, can serve as an example. In this shot, as in the other seven, Benning’s camera is stationary. The sounds of traffic crossing the bridge are relatively consistent and loud enough to keep our ears (and eyes) tuned to the bridge itself. However, after a few moments, my attention to the bridge and the traffic moving along it expanded to include gradual changes occurring on the water: boats of various sizes and speeds were moving toward, under, and away from the span. Often my vision intercut from the bridge traffic to one or another boat, and I was amused to see how far this or that boat had travelled while my vision had been seduced away for what seemed not quite enough time for the boats to have moved so far.

At a certain point, these first two foci of my attention were interrupted by my becoming aware of a detail subtle enough, at least at first, that I couldn’t help but wonder if it had been there, at the lower left corner of the image just below the bottom of the nearer bridge tower, all along—then again by a second detail at the bottom right corner of the image. Once I was aware of all the layers/sectors of the image, the corner images evoked, and maybe reference, the way in which, in classic landscape painting, the central vistas are often framed, left and right, by closer images that accentuate the deep space of the middle section.

I’m sure other film-goers will find their way around the Golden Gate Bridge image at different rates and in different orders. In any case, to assume that thirty seconds or a minute of this image tells its whole story is to miss what I see as the point of this shot and of Benning’s film, which offers us both a series of modern landscapes and various extended moments of visual and auditory discovery. I won’t spoil any further this shot’s or the films’ remaining opportunities for exploration.

I spoke to Benning before the premiere of EIGHT BRIDGES at Berlinale Forum. It bows stateside at MoMA’s Doc Fortnight next month. Following the interview text, which has been edited, I’ve included additional thoughts (this time, with spoilers) on the film’s political valence and the recent reception of Benning’s films outside of the U.S. and as part of the lineage of avant-garde filmmaking.

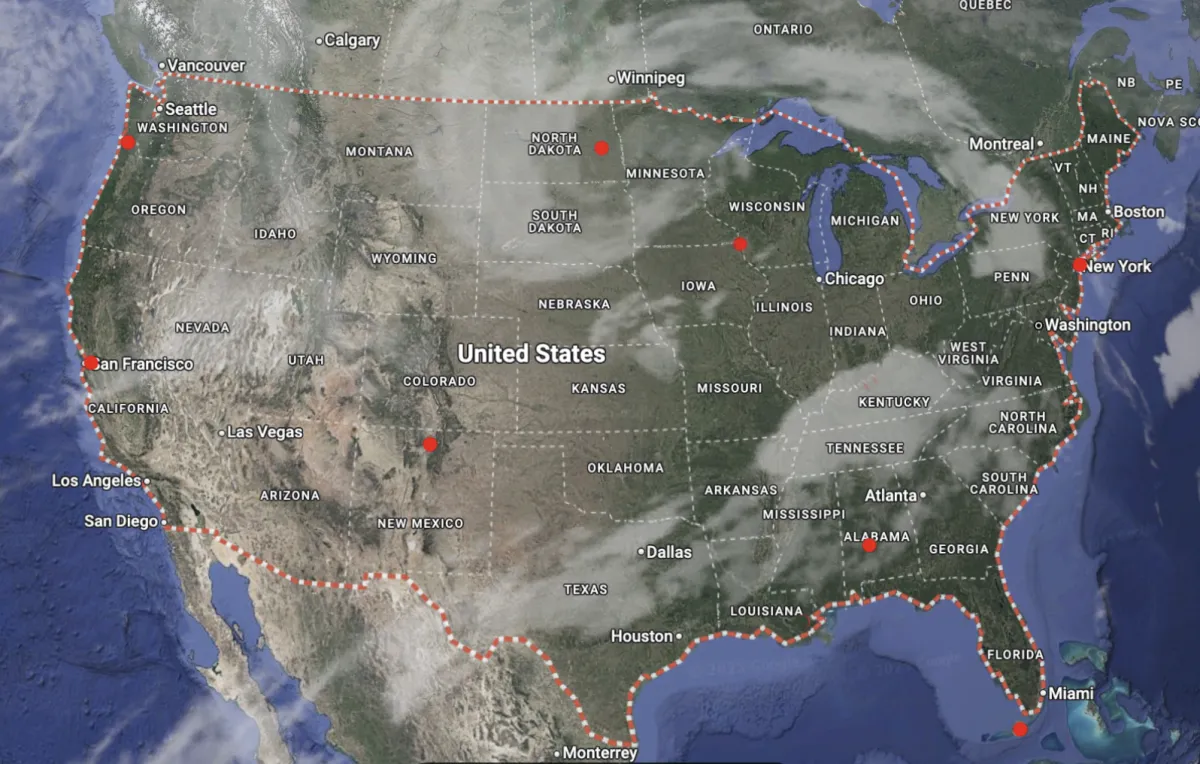

The red dots on the map indicate bridge locations. Courtesy of James Benning

DOCUMENTARY: James, I found EIGHT BRIDGES fascinating, particularly in the way that over the 10 minutes of watching each bridge, various discoveries and subtle surprises punctuate the experience of that bridge. I’m assuming that when you recorded a given bridge, you allotted more than ten minutes of shooting, maybe substantially more, then explored what you’d shot to decide which 10-minute section would be best to use.

JAMES BENNING: Yes, but most shots weren’t actually much more than 10 minutes. Before I made a shot, I’d already done a lot of advance planning. I’d decided to get to each bridge at a particular time of the day. And I paced my trip to each bridge in order to have ideal weather conditions for what I wanted to record on the day I’d arrive. For example, I wanted a different kind of sky at each place where I filmed. In 2001, for SOGOBI [2001], I spent three days on the Golden Gate Bridge, waiting for the right ship to film as it moved under the bridge. Generally I know before I arrive to shoot what I want and when I can get it.

But the fortuitous plays a bigger role than you suggest. The helicopter in the Keys, the ocean-going ship in Astoria, the boat up the Alabama River, the train along the Mississippi River, and a great sky with no train in North Dakota were not planned.

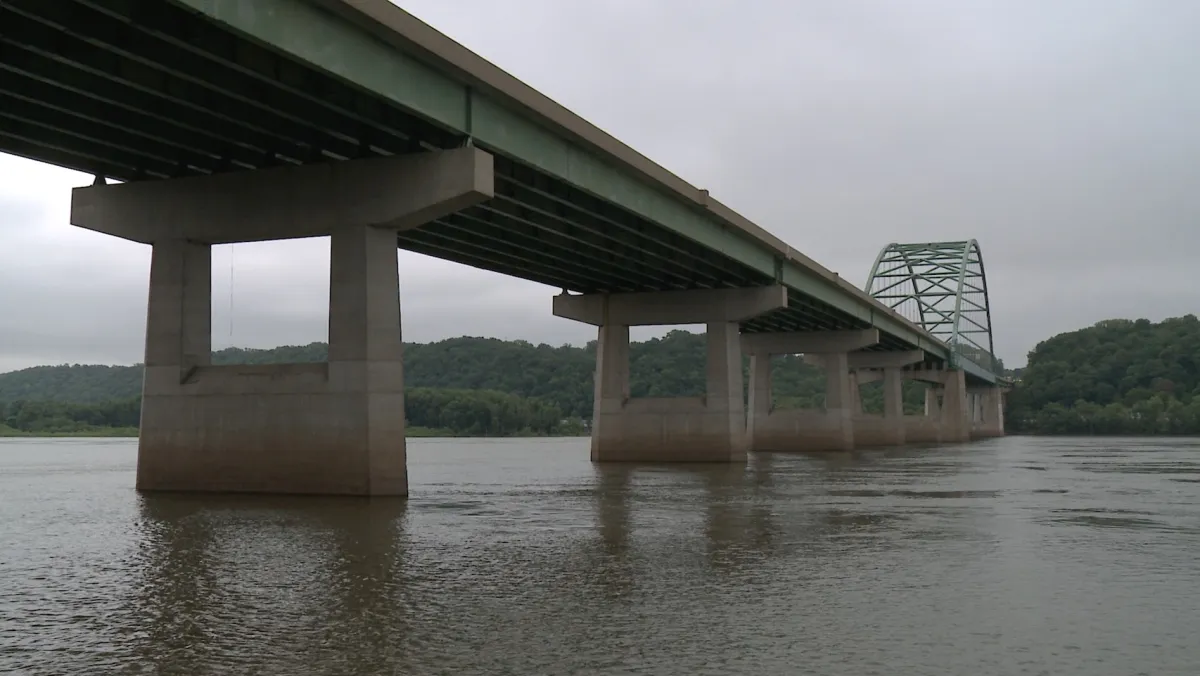

D: The allure of particular bridges is obvious—the Golden Gate, the Rio Grande Gorge Bridge (which I have fond memories of driving across), the George Washington—but in two instances the allure isn’t immediately clear. I looked up the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Alabama, only to realize (duh!) the ongoing historical complexity and importance of that bridge. But when I looked up the Dubuque-Wisconsin Bridge, I couldn’t understand why you’d chosen it.

JB: I have personal connections to some of the bridges. I first saw the bridge in Astoria in the summer of 1972, when Libby Taylor and I visited Astoria. Libby lived there as a teenager. At the time we visited, we were married and Libby was unknowingly pregnant with our daughter Sadie. I visited the Florida Keys with Bette Gordon in 1975 when the older Seven Mile Bridge was still in use. That’s the one you see in EIGHT BRIDGES—in my shot the newer bridge is hidden by the older bridge, although the trucks on the newer bridge can be seen and you can hear the traffic. The older bridge is used only for fishing now.

I wanted to film a bridge across the Mississippi, and I needed one in the Midwest. Hence the Dubuque-Wisconsin Bridge. I’m from Wisconsin.

D: The overall journey we imagine as we go from one bridge to another is evocative of your North on Evers [1991]. Originally, did you plan to make one long trip around the USA to shoot the film?

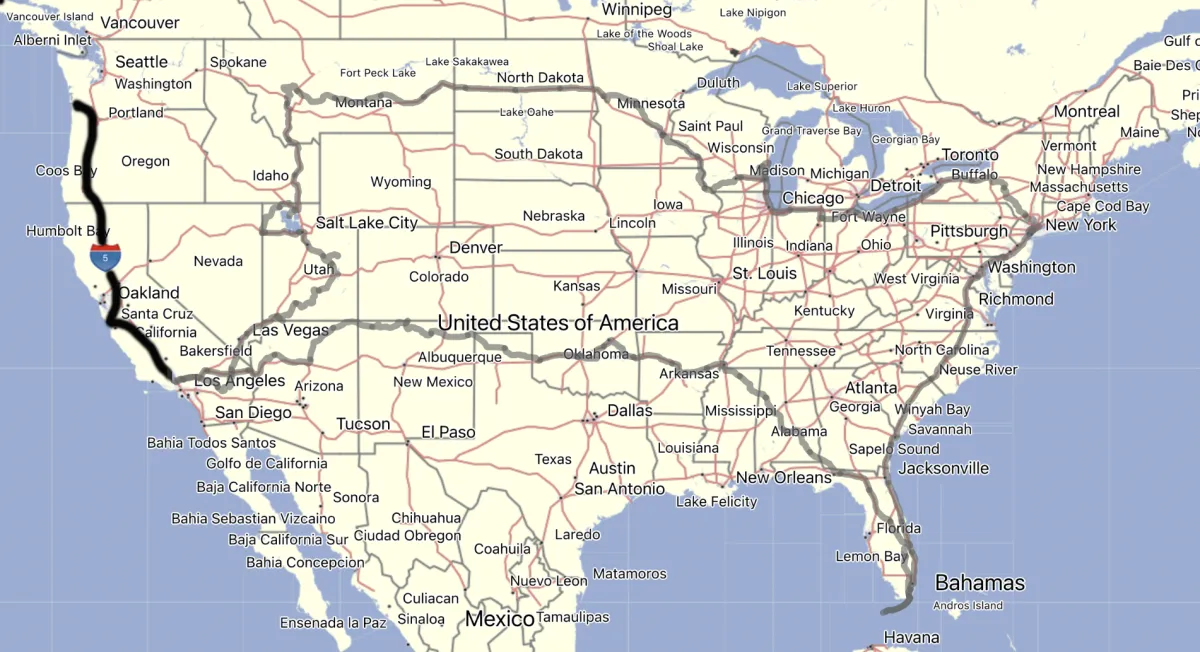

JB: I made two trips. The first one was with an ex-grad-student of mine, Yuan Gao. He drove his car. It was a test to see if I was up to doing what would need to be done for the film I had in mind. We drove to San Francisco first [Benning lives in Val Verde, near to where he teaches at CalArts] and shot the Golden Gate around 2:00 p.m. The next day we shot the bridge in Astoria at 4:30 p.m.

For the other six bridges my gallery [neugerriemschneider in Berlin] sent my gallery liaison, Dylan Lustrin, to help me. They paid for the car rental, hotels, gas, and food. We were on the road from July 2 to July 30 and shot in this order: Rio Grande Gorge Bridge, July 3; Edmund Pettus Bridge, July 6; Seven Mile Bridge, July 8; George Washington Bridge, July 11; Dubuque-Wisconsin Bridge, July 20; and the Hi-Line Railroad Bridge, July 22—I came to North Dakota to film a train crossing the Hi-Line, but the weather was threatening and I liked the sky. We did wait for a train, but I made my shot before a train arrived, because of the great sky.

D: We do hear a distant train near the end of that shot.

JB: I didn’t notice the sound of the train until I looked at the footage!

Though Benning has made many films, most all of them rigorously organized, the experience of EIGHT BRIDGES not only evokes his long-take serial films of the early 2000s, but also builds on them.

— Scott MacDonald

D: Were all the bridge shots recorded in sync? Often you’ve shot silent and recorded sound separately.

JB: Yes, everything was shot in sync. You can hear the sound of the train in the Mississippi River shot, but it’s very quiet, since it was so far away from the camera. In the Selma shot you can hear the sound of off-screen fans from the St. James Hotel air conditioners.

D: Did you always make only one shot of a bridge, or did you make several shots of some bridges and choose what you saw as the most useful one?

JB: I made only one shot at each bridge, except the Golden Gate. That was the first bridge to be filmed. There was a heavy wind. Yuan Gao held down the tripod and I steadied the camera. Then we drove to Astoria to do the second bridge and filmed that with just one shot. On the way back we stopped at the Golden Gate again and shot it two more times. But in the end, I used the first shot and scrapped the others. During the second trip, I only did one shot at each bridge.

D: Why eight bridges? Were you concerned about the length of the piece?

JB: Other lengths would have worked. I just thought EIGHT BRIDGES made a good title. I’ve done Two Faces [1973], Two Cabins [2011], TEN SKIES, 13 Lakes, Twenty Cigarettes [2011] and two moons [2019].

D: Why are some of your titles, and “EIGHT BRIDGES” in particular, all caps?

JB: Especially in italics, the title looks like the structure of a bridge.

The lines on the map reference Benning’s two trips. Courtesy of James Benning

In EIGHT BRIDGES, Benning returns to a fundamental element of cinema (whether analog or digital): a single shot plus a cut to another shot. The edit is emphasized in two ways. Each shot is long enough so that once we’ve become aware of the obvious and subtle dimensions of that image, we cannot help but try to imagine what the next image will show us. And Benning expands the cut by using five-second moments of darkness as bridges between each pair of shots.

EIGHT BRIDGES tempts us to learn more about a series of particular bridges and their geographic and historical locations, and it teases us to notice and consider details within each shot that our impatience with films that don’t focus on character and narrative can blind us to. Benning’s films help to retrain our perception and our patience so that we can be more aware, both within cinema and within our surroundings.

EIGHT BRIDGES is as expansive as it is precise, both in its serial design and in its scope. Andy Warhol’s films (particularly, Kiss [1964] and the various compilations of his “Screen Tests”—e.g., 13 Most Beautiful Women, 13 Most Beautiful Boys [both 1965])—and Yoko Ono’s No. 4 Bottoms (1966) seem in the background of Benning’s serial design. In its geographic scope, EIGHT BRIDGES has much in common with other documentary films that present a series of specific aspects of a particular region or the globe, including Lois Patiño’s Costa da morte (2013), Michael Glawogger’s “Globalization Trilogy”: Megacities (1998), Workingman’s Death (2004), Whore’s Glory (2011); and Nikolaus Geyrhalter’s panoramic films: Our Daily Bread (2005), Homo Sapiens (2016), Earth (2019), and Matter Out of Place (2022).

A final note. Benning’s films are often subtly (and sometimes not so subtly) political. The choice of the Edmund Pettus Bridge for EIGHT BRIDGES is an instance. Completed in 1940, the bridge was a celebration of Edmund Pettus, a former Confederate brigadier general, U.S. senator, and Grand Dragon of the Alabama Ku Klux Klan. Twenty-five years later on March 7, 1965, it became a pivotal site in the Civil Rights movement when state troopers brutally attacked peaceful voting rights marchers on what became known as “Bloody Sunday.”

In recent decades, Benning’s work has been celebrated more frequently in Europe than in North America. Especially during the past year, the Trump administration’s international stance with regard to Europe seems to be endangering NATO. When Benning was asked for a statement to accompany his upcoming screening at the Forum in Berlin, he wrote, “It seems to be the time to consider bridges”—presumably referring not just to modern American bridge architecture, but to our current political environment.

EIGHT BRIDGES is, by turns, meditative and contemplative. By asking us to remember and enjoy the fundamental pleasure of cinema, within the continual barrage of commercial advertising and of films/shows made and marketed for easy consumption, plus continual Capitalist overloading of our perceptual faculties, exacerbated by the expanding (and visually contracting) dominance of cellphones, and the concerning political tension between Europe and Trump’s “MAGA” America, Benning offers an extended moment, if not of therapy, at least of quiet thoughtfulness and awareness—and cinematic pleasure.