Lost and Found: Charlie Shackleton’s Found Footage 35mm Film ‘The Afterlight’ Disappeared for Weeks

By Dan Schindel

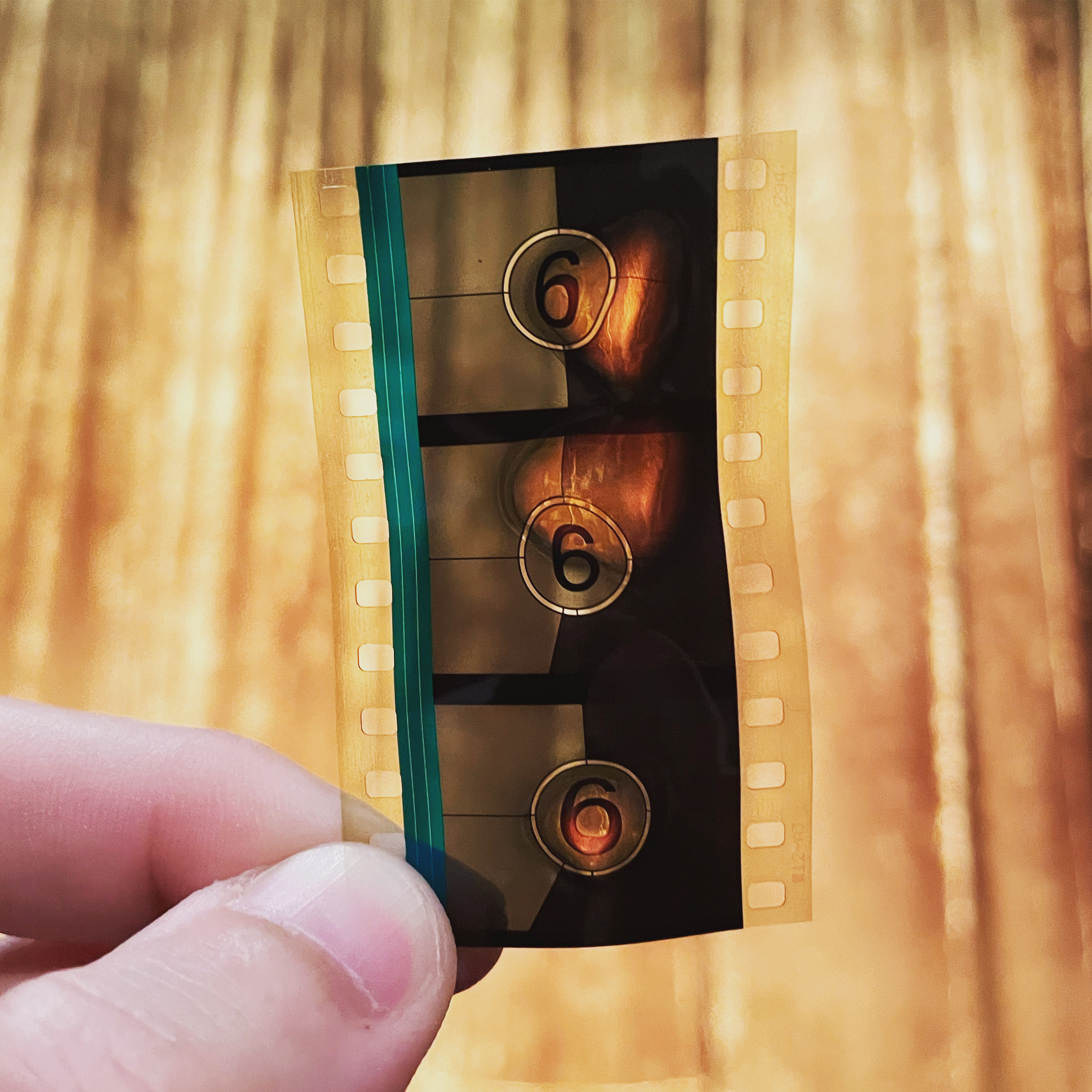

Still from The Afterlight. Courtesy of Charlie Shackleton.

Charlie Shackleton describes The Afterlight as “a film that’s designed to be lost.” A meditation on impermanence and mortality, consisting of imagery of deceased performers taken from hundreds of films, the all-archival feature incorporates that idea into its very being. It deliberately exists as a single 35mm print that will naturally degrade over time and with every showing. When that print is gone, no more Afterlight.

But recently, the film was lost in a different way than intended. Since its premiere at the BFI London Film Festival in 2021, it’s been on a continual touring schedule, shipping to various venues around the world. Sometime in late May, in transit from the UK to Portugal, the print went missing. Fortunately, less than two weeks after Shackleton announced this, he had a happy update: The Afterlight had finally turned up at its destination, just much later than it was supposed to. In the interval between those two announcements, Documentary spoke with Shackleton over Zoom about what the loss (even temporary) of The Afterlight means for the overall project. We then spoke again after the film was rediscovered. These two conversations have been combined, edited, and condensed for time and clarity.

DOCUMENTARY: How are you feeling? It’s been about a month, right? Are you in the acceptance stage?

CHARLIE SHACKLETON: I feel oddly sanguine, so maybe I’m not even at acceptance, maybe I’m still in denial. I do feel like there’s still a reasonable chance it’ll show up eventually, but even if it doesn’t, I feel oddly resolved or reconciled to that reality. But maybe it just hasn’t hit me yet.

D: For people who don’t know, what are the actual logistics of shipping film reels?

CS: The typical way that a film print is shipped is in Goldberg cases, which are those octagonal containers you sometimes see in cinema lobbies—or more likely cinema museums, at this point. My print had a slightly more heavy-duty bright orange Peli [Pelican] case. In theory, it’s harder to lose and better protected against whatever conditions it may currently be sitting in. But obviously it’s a big wide world full of enormous FedEx distribution centers, and these things do still get lost.

D: It was traveling to Lisbon. Is there anything to the story besides “FedEx lost it”?

CS: The last screening it had was at the Hyde Park Picture House, which is a beautiful old cinema in Leeds in the north of England. There was a good couple-of-weeks gap between that and the next screening, which was due to be at the Cinematheque in Lisbon. It was collected from Hyde Park by FedEx, and it definitely made it as far as the Bradford sorting office, and that was the last time it was scanned. For a while, there were just unspecified delays. And then once FedEx actually looked into it, they realized they didn’t know where it was. There was a brief claim that it had turned up at Portuguese customs, but then that was retracted. Subsequently, Portuguese customs said they never had it.

D: It isn’t unusual for prints to get lost in transit. I’ve been to screenings where they had to show a DCP because the reels were delayed. Do you have any recourse for resolving a problem like this?

CS: Essentially not. I wasn’t the one who arranged the shipment, so most of the communication with FedEx has been happening on my behalf by the cinema. I think they phoned FedEx and made an impassioned case that this was a particularly irreplaceable item. I think FedEx did agree to move it out of “lost” status and into whatever is one step down from that, which I guess is “We’re still having a look.” But I don’t really know what that means, if there are people in these sorting offices looking around, seeing if they can spot it. We sent them photos of the case.

Based on stories people have told me, if these things turn up at all, it’s months or years later when someone’s clearing out a particular room and stumbles upon it. If that happens, the case has my name and address and phone number on it, and they will hopefully have a way to get it back to me. But I have no sense of how likely that is.

D: Besides your contact information that’s on the packaging, what’s in the package that indicates what the film is? Is that not even a concern, since generally the only people handling the film know what the deal is?

CS: Yeah, exactly. I mean, it’s four reels in a case, but the average person opening it up might not even know it was a film print if they have no context for what that looks like. If you open the cans, you can see the physical film, and most people could probably work it out by that point. It says the name “The Afterlight” on the cans, so I suppose if they Googled it, they’d find out what the film was. And my name and address are on each of the cans as well.

All of this is leading me to have a slightly greater belief that it will show up, however long it takes, because I just figure: Well, it exists somewhere. It has a physical form, unless it fell off the back of a plane or into an incinerator. I’m cautiously optimistic, whether that’s foolish or not.

D: You’ve thought through a lot with this project. Had you considered the possibility of something like this at some point?

CS: It was always a possibility. If anything, it seems the more likely avenue for the film to become lost, at least in its early years. Typical damage to a film print through projection is fairly incremental and minor, especially these days, when the only people still doing analog film projection are pros and people who really care about it. You don’t really get so many terrible projection mistakes anymore. I always knew that if the film was going to become un-screenable in its early life, it would be through being misplaced as opposed to damaged.

That said, the more times I shipped it without incident, the more confident I became in that process and the less I worried when it was out of my hands. If anything, it seemed less loss-prone than all the other films I’ve made, which exist on hard drives in various places. It’s a bit of an act of faith that when I plug them in, the film’s still going to be there, the file’s not going to be corrupted, and it’s still going to play or be able to be sent wherever it needs to go. By contrast, The Afterlight felt so material, so literally weighty and bulky, that I couldn’t quite imagine it going missing.

D: Had the film shown any evidence of deterioration over the course of its screenings to date?

CS: Yeah. So, as is typical with a film print, the damage that had amassed thus far tended to be at the beginnings and ends of the reels, because those are the parts that get handled most. It had all those telltale speckly patches every 20 minutes, as well as some more concrete damage. There were some pretty gnarly track lines at the beginning of the second reel, which would’ve been the result of some sort of misalignment with a projector. One projectionist burned the countdown on the first reel and then didn’t confess to it. I only found out several screenings later, when another projectionist pointed it out. They clipped out the three affected frames, which incredibly happens to be three sixes. I had this quite demonic little memento of these three burned sixes. But the print is still in pretty good condition.

D: The Afterlight is a sort of synecdoche for the broader experience of physical film—of deterioration, exhibition, preservation. Films being lost is also part of that experience. But so is rediscovery. That would be a fitting further development—one that I think we’re all hoping for.

CS: Totally. I mean, it feels like a fitting new stage in the project’s life for it to have become lost. I have obviously also imagined the possibility of this eventual rediscovery, which I think for it to have its real mythological impact needs to be at least a year or two, maybe decades down the line, as opposed to next week, in which case I think people would feel like I’d made a bit of a song and dance about nothing.

It’s a strange thing, because even though it is now lost, it’s hard to say what real difference that makes from when it wasn’t. Because there was only one print, the odds of me seeing it again anytime soon were quite low. The odds of you seeing it again anytime soon were quite low. The people who it’s truly been lost for are the ones who were going to see it in Lisbon and didn’t, and then the people who would’ve seen it at the two or three screenings I had booked in for the coming months. Maybe this is why the emotional impact of it being lost hasn’t kicked in, because its being found was so contingent already. I guess the prospect of rediscovery is similarly strange, because if it’s rediscovered tomorrow, what does that mean to you until it comes to New York? Is there any real difference? The film already had such a strange, tentative existence.

D: I can’t fully recall what contextualizing information there is within The Afterlight itself as to what its deal is—whether there are titles and such. If your contact information was somehow fully separated from the reels, how easy would it be for someone who found them to trace them to you?

CS: On a physical level, the four reels are numbered—not just on the cans, but on the film itself. Anyone who found it would in theory have the information they need to screen it. There’s a title on the front, there are credits on the end. In some ways it looks like a traditional film. But as to what it would mean to someone who found it, that is quite reliant on the information that remains available about its creation and its context and its meaning.

Funnily enough, a couple of months ago, a friend gave me a big box of 16mm prints she was getting rid of. I had a couple of friends around, and we sat in my living room and we screened a few of them as a potluck movie night. One of them was a student film from 25 years ago that was actually great. It was called Thread, and we looked up the director to find more information, because it was just like the scenario you described. It had credits, but there was no real indication of the context of its making. We found out that the director, Susannah Gent, is now a film professor at a university in England. I got in touch with her, and lo and behold, it turned out she had been looking for the print for years. So I sent it back to her. Having even the scant information about the film available online meant I could connect it to its wider context. Obviously, I’m hoping the karmic value of me having done that just before my own print went missing is going to see its return to me.

D: If nothing else, I hope this story raises awareness about how tenuous so much of our media is—even if it doesn’t exist on a single print.

CS: I hope so. It’s funny, actually, because it’s now on Wikipedia’s list of lost films, which basically ends in the ’80s, with my film as the lone example from recent decades. But we know that’s not true. More films are being lost now than at any point in the last 50, 60 years. It’s just that we don’t know in most instances, the sheer number of even fairly significant independent festival circuit movies that exist solely on a hard drive in someone’s office somewhere, and next time they go to look, it may not be there. The question isn’t whether they’re lost, but how many are.

***

Not long after, the film reels were found. We hopped back on Zoom for a brief follow-up call with Shackleton.

D: Congratulations! That didn’t take nearly as long as we feared.

CS: I can’t even remember what the differential in days was between us talking and it turning up, but it felt like a matter of minutes.

D: Were they able to provide any details on why it was waylaid and where it had been during that time?

CS: Not yet. I’m going to try to find out, but I imagine it’s just the mysteries of the FedEx system. But now it’s at the cinematheque.

D: Will the theater still be able to show it?

CS: I think they’re hoping to. It’s still there, but obviously the screening date was weeks ago, and they’re going to try to squeeze it into their schedule.

D: We actually didn’t touch on this before, but how do you insure the print when you ship it?

CS: I always just get—and encourage other people to just get—the minimum coverage, because the more value you declare, the higher the cost of shipping. Ultimately, it’s literally irreplaceable, so it would be nice to have a big payout if it got lost, but that would come at the cost of every single instance of shipping it being vastly more expensive. So it would’ve been 200 euros, whatever the standard coverage is for a FedEx shipment.

D: How has this episode impacted the film’s planned tour?

CS: Fortunately, there was a gap in the screening schedule, so the only one it missed was the one it was on its way to. And like I say, hopefully they are going to be able to do that, just delayed. It’ll ship straight on from Lisbon to the next one. The film’s been found, but not in a sense that I really have any physical relationship to. Because typically it goes from place to place, and only if there’s a big gap does it return to me and live behind my sofa.

D: Now that this has happened, do you feel any trepidation about the idea of shipping it again? Are there any further precautions you’ll take?

CS: Weirdly, I think maybe I’ve become cocky through it having turned up, but I don’t feel that fazed by it. My producer is absolutely adamant that we buy one of those AirTags and put that in the case, though. But I don’t know if you’re allowed to do that, if that interferes with FedEx’s system in some way. The way those work is they use iPhones in the vicinity to identify where the tag is. But then, I think because they don’t want anyone to use them to stalk people, if one’s near your iPhone for more than 10 minutes, you get a notification. So possibly that would mean that a FedEx driver would be bombarded with notifications. But then maybe that’s happening left and right. I’m sure we’re not the only people who thought of this.

D: As I said before, the film is a synecdoche for the wider experience of celluloid. And now we’ve seen in miniature the process of a film being lost and found, which is kind of beautiful

CS: Yeah. Very miniature, obviously. It felt quite humiliating when the Wikipedia entry got updated more or less immediately after I put on Twitter that the print had been found—“However, it was found later that month.” I feel the urge to clarify that it was lost for more than a month; I just waited a while before I told anyone. But yeah, it does look like I made a fuss about nothing. It’s probably the shortest period in history that a film has been lost.

Dan Schindel is a freelance critic and full-time copy editor living in Brooklyn. He has previously worked as the associate editor for documentary at Hyperallergic.