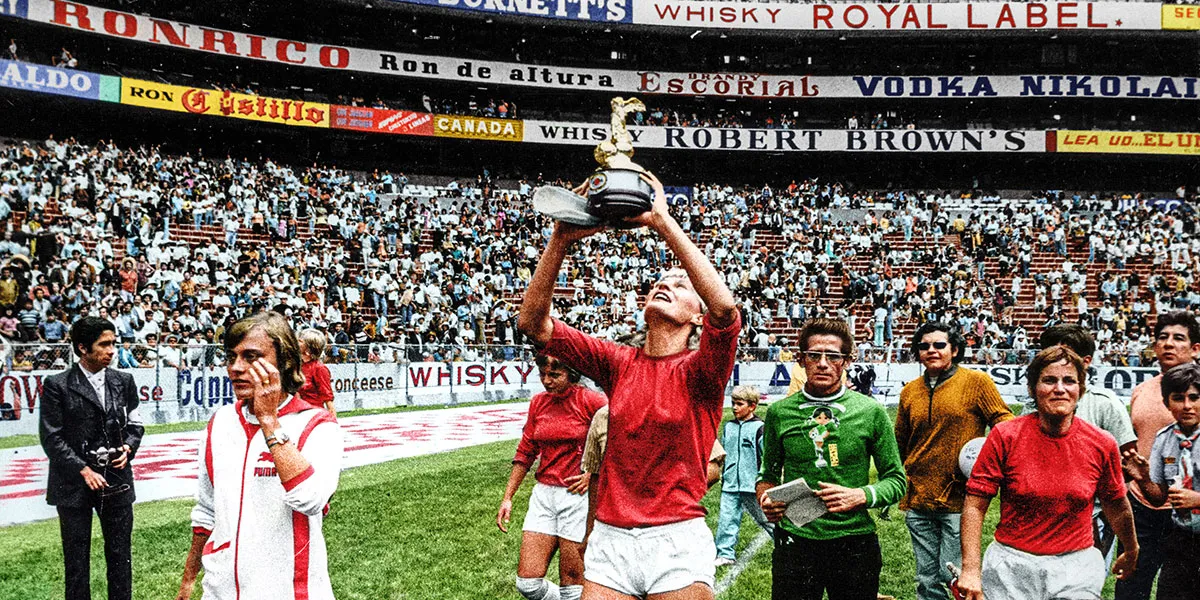

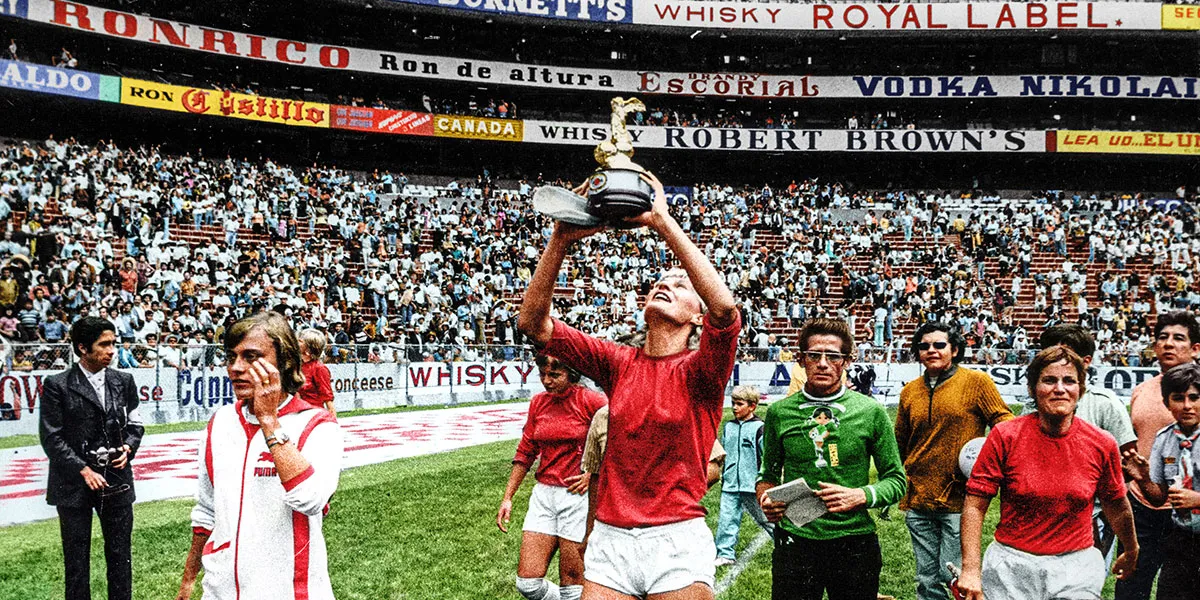

Film still from Copa 71

I started playing soccer (football! Sorry, I’m American) when I was four. My mom was my first coach. Growing up in Pasadena, there weren’t many Black girls playing the sport, but I loved the game. From AYSO (American Youth Soccer Organization) to 4-year high school varsity, from club teams to going out for my college team, soccer was and still is life.

It wasn’t easy. It was even brutal at times. You cry because you didn’t make the team because of apparent racial bias. You must prove you belong on the team more than your teammates do. You’re told you should lose weight or watch what you eat. You’re told, not asked, to learn another position because they have enough good players. You have to drive an hour and a half away to play for a high-caliber club team because you didn’t “fit in” with the ones nearby. You’re strung along, only to be told you are just as good as the rest of the team, but they need someone better. You love the game so much that you deal with the negativity and keep playing wherever possible. You have such a passion for the game that it’s worth dealing with the negative as long as you get to play.

1999, I attended my first women’s professional soccer match at Rose Bowl Stadium. A location I grew up around. A place I had played plenty of AYSO games in front of. 1999 and the FIFA Women’s World Cup will always be the mark of the overwhelming push to be like my heroes - Briana Scurry, Mia Hamm, and Brandi Chastain. Watching documentaries like HBO’s Dare to Dream: The Story of the U.S Women’s Soccer Team (2005) and This is Football’s episode “Belief,” co-directed by Rachel Ramsay and James Erskine, are reminders of the struggles women have been facing in women’s sports, mainly women’s soccer, since before I was born.

From being the only Black girl on the team, overshadowed by other players, audiences, and media, to fighting for the same opportunities as the men for fields, pay, and equipment, the women of the soccer world have had an impressive rise, and the U.S. has seen a growth of the game overall. Where did this rise and growth stem from? Some say it was the 1999 Women’s World Cup. Others say the 1991 tournament. Copa 71, Erskine and Ramsay’s new project, which opened TIFF Docs this month, sheds light on the subject, telling the story of the 1971 Women’s World Cup and how it was erased from history. This tournament included teams from around the world, playing in Mexico City with record crowds, and it was written out of sports history. I related to it more than I thought I would. Full of archival footage and interviews with players from then and now, Copa 71 is a historical addition to the legacy of women’s soccer.

Truly in awe of the secret history behind Copa 71, I talked to Ramsay and Erskine about the making of the documentary and what might never be resolved. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

DOCUMENTARY: Did you play football growing up?

JAMES ERSKINE: Not consistently with a team. The league played on Sundays, and my parents didn’t favor that. They were more in favor of me going to church. I played for the church team sometimes. My kids are good footballers. I generally played on the wing.

RACHEL RAMSAY: I didn’t play football or any sport. And I didn’t grow up as a football fan. I’m coming at it from a different angle as to why and how I find this fascinating.

D: Why this story? Why this sport, in general?

RR: I’m a very curious person and fascinated by what makes other people tick and what drives people to do what they do. I find it particularly interesting in sports because it’s never been a driver for me, so I want to know why people are so passionate and how it can shape the world so much, which it clearly does.

We made a series together a few years ago, This is Football, about emotion and the geopolitics of football and how it’s shaped so many individual lives and societal structures. If it's true that that sport crosses all boundaries, languages, borders, and it’s universally accessible, where are all the women? Because I came from a non-football background, I could ask that question and say, “I don’t understand. Where are all the women?” We came across this story from our producer, Victoria Gregory, who heard it and thought, Oh my gosh, there’s something in this as soon as she heard it.

D: You heard about it and did the research. What was that process like?

JE: Victoria’s husband had heard a radio show in England, and the England women’s team had been reunited on television for the first time in 50 years on a telly show called The One Show. It’s like an evening magazine show. One of their items was this 8-minute piece where they said there was this tournament, and here are the women together, and they haven’t seen each other for a number of years. That was the only thing we could find that tangibly existed.

RR: Tangibly is a good word for that because, unusually now, what we had from research was tangible newspapers. That was the only place the story existed, in newspapers in 1971 that had been kept by the players in souvenir scrapbooks. They brought those to us. We started with those, and we realized it went around the world. It expanded and expanded, and we went to each of the countries. Our researcher, Ella, reviewed all the physical copies of the 1971 Mexican newspapers in Spanish to build match reports. That’s how we know what happened in each match, to piece the footage together.

D: Archives and documentaries are top of mind right now. What was that archival process like for you?

JE: A lot of people and a lot of different countries. We knew we would be looking in the UK, Mexico, and the major film archives, but we even had to do a lot more deep dives internationally to build up that montage sequence. That footage is from Switzerland, Germany, France, Italy, the UK, and the Netherlands, just to make that. The challenge was to find footage that was respectful. There was some Pathé stuff that laughed at women. The male gaze was applied to them because the men controlled the media, so we had to fight through it. The tournament had female and male commentators who treated it well.

RR: They treated it with the same respect that they did for the 1971 Men’s World Cup. They wanted to see the Mexican team play football, and it wasn’t a consideration that it was women’s football. The Mexican national team is the Mexican national team.

JE: Yeah. We talk about the male gaze, but there’s also this European/American gaze on football that suggests that Mexico would not be sophisticated enough or would be some sort of backwater.

D: At the beginning of the film, you showed Brandi Chastain footage of the ’71 Women’s World Cup, and she was blown away. With the 1999 team winning the World Cup and the audience support in the U.S., I’m surprised there was no mention of the 1971 Women’s Tournament.

JE: We sort of know quite a lot about 1999 because we made this other film about that. 1999 was a big shock when it happened for women’s soccer. The women had to go out there and support it on the ground. There was no great plan to make that into a big event.

RR: The first time the women’s league in the UK has become fully professional was in the last 5 years. It’s so recent!

This whole idea about women’s football being created in the '90s, it’s like, yeah, it was created in the '90s, but it’s the 1890s. There’s a hundred years of history that has been not just erased, but it doesn’t exist. So that’s part of why we see this one as just one tiny little block. That’s why we were so keen on focusing on the tournament itself from the beginning. We’re not suggesting we made a film about the history of women’s football.

JE: But it’s also true that people, only in the last couple of decades, have treated sports seriously as a cultural phenomenon. It’s being investigated in books. In football you can literally chart the first book about football, which was a book called All Played Out, which basically starts the idea that you can write intelligently about soccer in the UK.

D: 1999 was my first World Cup. I was young. The newspapers featured Brandi Chastain and the whole sports bra debacle, where she took off her shirt and celebrated in her sports bra. The media went crazy about her bra and her physique, even referencing it as an athletic striptease. In Copa 71, there was a line about how the men came to see the women in shorts and to see how crazy or good they were, like a dog walking on its hind legs.

RR: That line! In the early days of research, we were writing up the first doc treatments, I had that on a post-it note on my desktop. “Women’s sports is like watching a dog walk on its hind legs. It’s not well done, but surprising to see it done at all.” Every time I saw it, it was like a gut punch. I was like, right, gotta make this film.

JE: Sports films boil down to great structure. You’re generally rooting for someone. What we had to be really judicious of with the edit was we didn’t want anybody to watch the film and be rooting for one team. We could have chosen that we wanted to go with the Danes all the way or the Mexicans. But we want people to understand it’s a whole movement. They’re playing together! You can only play football if you’ve got an opponent. You should like your opponent because they are helping facilitate your joy.

D: I was expecting a comment from FIFA. Did you think about or try to get something from them?

JE: Yeah, FIFA’s position is that they don’t really talk about it. It had nothing to do with them, so they have no comment.

We are not in any way anti-FIFA. There are obviously some strange statements that have been made in the last World Cup, but FIFA is pushing women’s football now, and they have been in support of it. The misogyny is clearly still there. What they aren’t necessarily good at is saying sorry for the past, partly because they say well, it’s not our mistake what happened in the past. But we all know that’s not an answer.

RR: That’s not an apology. That’s not an acceptable version, to say we’re not going to make an apology because it wasn’t our fault. This is not really the point. It’s still gaslighting. It’s the lack of accountability, the lack of responsibility taken. People are benefiting from the existence of women’s football now. So that’s great, okay, but then you can’t have a narrative where it just didn’t exist before ’91.

D: Right. Given the last two World Cups and the social change that's happening, what do you hope this film will accomplish in terms of the narrative around women’s football?

RR: When we started making this, there were the obvious questions of why are you choosing this one tournament? Why not talk about the whole history of women’s sports? We need many films about all the different parts of it.

I am so proud of our team that has been part of this. In each country, there were individual academics, writers, and journalists who had been plugging away for years, quietly doing their research. We worked with a specialist consultant named Jean Williams in the UK. All the academics and journalists we worked with are all in different places, and they are given special thanks at the end of the film, but bringing all those women together and making it on an international scale, there was an interest in somebody doing that.

We talked about how we structure the film, and a lot of it was around the themes that we wanted to address, like women’s physicality and controlling that and passion.

Our researcher, Ella, she’s brilliant, and—when we were coming up with ways to end the film, I said I really wanted to get the England team going to a current match. And because of the connection with Newcastle in the film, I thought, wouldn’t it be amazing if we could take them back to St. James’ Park and they could watch the women’s match at St. James’ Park now? Ella’s like, but the women don’t play there. I was like, what do you mean the women don’t play there? She’s like, no, they play in that little stadium down the road. I was like, What? I couldn’t even create the dream scene because it doesn’t exist. It’s mad.

JE: It makes absolutely no sense. Of course, it’s a little more cost for the stadium, but the stadium is a lavish cost. You’ve got to maintain it anyway. You’re literally preserving the grounds and the field for male privilege. You’re basically saying men can work on this, women cannot.

D: What are your thoughts on the ease of finding distributors and what that process looks like?

JE: To be fair, we’ve only just started. TIFF was our premiere. We brought it here to show to distributors. The film is also produced by my company with Victoria, and over the years, we’ve made about 15 or 16 feature docs. We are pretty confident in finding distribution. What we then need to do is make sure the distributor really understands how to distribute and carry the message through. That’s always a challenge. We had a film five years ago, Maiden. Sony Pictures Classic did a brilliant job of releasing that film. They were the only ones who really wanted to drive the message. We took a lower offer from them on the basis that would give the story more profile.

That’s the wonderful thing about cinema, it’s a collective experience. Just like sports. It's great to watch this movie at home, but it’s also great to watch it with a crowd of people who cheer when you cheer. That’s what you go to football for. You sit with different people who are going to share your emotions. You don’t go because it looks better from the stadium.

Catalina Combs is a Marketing and Communications Manager at IDA, a freelance journalist, and film critic. The majority of her work can be found on the online publication Blackgirlnerds.com. She is a member of critics' associations, including the Critics Choice Association, African American Film Critics Association, the Online Association of Female Film Critics, and the Hollywood Creative Alliance, as well as a Rotten Tomatoes-approved critic.