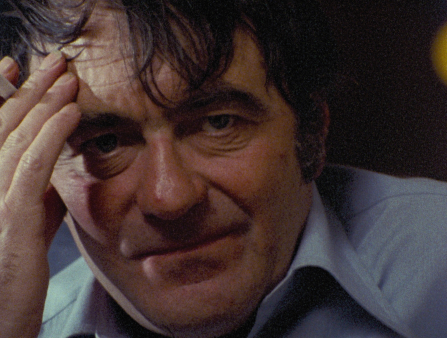

Guillaume Ribot’s All I Had Was Nothingness watches how Claude Lanzmann went about shooting Shoah (1985), which is not a film that necessarily invites such scrutiny, partly because of its gravitas, but also because the opus in a way is already a chronicle of Lanzmann’s search. But Ribot, a French photographer turned filmmaker who has worked extensively with archives, went back to the 220 hours of outtakes to craft a stand-alone behind-the-scenes look at Lanzmann’s filmmaking process from 1973 to 1981, delving further into his thoughts through a voiceover drawn from his own writings (and delivered by Ribot).

It was Lanzmann’s 2011 recollections of making Shoah in his memoir, The Patagonian Hare, that originally inspired Ribot to make All I Had Was Nothingness. The film shows the context for Shoah’s landmark sequences of survivors Abraham Bomba and Simon Srebnik, and Nazi guard Franz Schalling, as well as Lanzmann’s conversations with Polish farmers who lived near concentration camps. We see Lanzmann being fitted for a wire to record Nazis clandestinely, and what happens when one Nazi’s family suspects as much.

Beyond its chronicle of a filmmaker, All I Had Was Nothingness taps into the power of Shoah simply because, explicitly or not, it functions as a kind of abridged companion to Lanzmann’s monumental classic. Ribot’s film had its world premiere at the 75th Berlin Film Festival, where Shoah was also screened on the 80th anniversary of World War II’s end (with Claude Lanzmann’s partner, Dominique, in attendance). The film is the centerpiece screening at the New York Jewish Film Festival next week. I spoke with the filmmaker in Berlin and later over email too about approaching Shoah, his use of the outtakes, and what he learned about Lanzmann. This interview has been edited.

DOCUMENTARY: When did you see Shoah for the first time in your life?

GUILLAUME RIBOT: I didn’t see it when it was theatrically released in 1985 because I was too young back then. I saw it in the beginning of the 1990s, when I was still a photographer and not a filmmaker. I knew almost nothing about the subject, and I was deeply touched, from a physical point of view, by the experience and the power of those images. Ever since, I’ve been working on the Holocaust for 27 years as a subject matter. I’ve seen the film quite a few times, and since it lasts nine and a half hours, it means I have dedicated quite a bit of my life to the film. At a certain moment, I made a storyboard of all the shots of Shoah, and it really prompted me to become a filmmaker. It’s a film that is a physical, visual experience that deserves to be in a cinema.

D: What were your starting coordinates in terms of encountering the history of the Holocaust? Many American students, for example, read Elie Wiesel’s Night, but what were your first encounters in literature or film?

GR: In France, all students between the age of 12 and 15 had to watch Night and Fog (1956) by Alain Resnais which is the exact opposite of Shoah. Shoah has no archival footage, and it makes an intellectual appeal. Alain Resnais’s film, which is very important indeed, is a mix of archival footage of the deportation of the Jews and the deportation of politicians. It caused a scandal in France and was rejected by the Cannes Film Festival for one reason. In the first frame, you see a gendarme watching over a camp in France. So the government forbade the film from Cannes. So the first experience with the Holocaust I had in the 1980s was with that film, which doesn’t explain anything and just appalls you from beginning to end. These are images of English bulldozers, not even Nazi bulldozers, pushing bodies into common graves at Bergen-Belsen to avoid disease. And immediately the brain imagines false things, whereas Shoah does the exact opposite. That’s why Shoah is a cornerstone, in not showing archival footage in the form of iconic images that we are familiar with.

D: Could you talk about your personal connection to the subject? Your first film, Susi’s Notebook (2013), was made using your family’s archives.

GR: I’d never have thought of becoming a film director—and therefore wouldn’t have made All I Had Was Nothingness—if I hadn’t found a photo in a shoebox at my late grandmother’s house in the early 2000s. In this photo, taken in the summer of 1943, a young peasant woman is surrounded by children. She lived in a little village (Lafitte-sur-Lot) in the southwest of France and welcomed children to her farm. Their parents hoped they would be better nourished in the countryside. The parents of Jewish children hoped that their Jewishness could be hidden. My grandmother, Paulette Morichon, spoke just a few words to me before slipping into the distant world of Alzheimer’s disease: “You know, I hid Jewish children during the war.”

That photo is what led me to investigate my grandmother’s village. I couldn’t find the two Jewish boys in the photo, for whom I had only the false first names. But this magnificent image did put me on the trail of two other children not in the picture: Susi and Elise Feldsberg. They were 11 and 9 years old. At my grandmother’s brother’s house, I found Susi’s school notebook, a simple schoolgirl’s notebook that reveals all the humanity of this little girl. She wrote her last essay in June 1942. Two months later, on August 26, 1942, Susi and Elise were arrested by the French police and deported two weeks later to Auschwitz. They were immediately gassed on arrival. I traveled across Europe to tell their story and give them back their names.

Stills courtesy of Janus Films.

D: For All I Had Was Nothingness, did you always plan to use solely outtakes from Shoah and no other elements besides the voiceover?

GR: Very early on I had the intuition that I should only use the outtakes, because my film cannot be labeled as a documentary in the classic idea of a documentary with inserts of scholars and other talking heads. I just wanted to show Claude Lanzmann the filmmaker, at work on the making of his own film. I did some research in the beginning because I wasn’t sure I had enough footage for the structure that I had in mind to work. At the time of writing the script, I had no idea if I had all the connections that I needed—for the use of hidden cameras, did I have enough takes to show that? It’s a film that doesn’t have a single documentary shot in a way—it’s a very hybrid format. It’s closer to fiction because it’s a sort of police investigation, a road movie.

D: Since you have seen all 220 hours of the rushes, were you able to discern what sort of choices Lanzmann was making in editing together sequences?

GR: My choices are different, and the films don’t talk about the same thing. Shoah is a film about how death is radical. My film is about how life can be radical. And it’s the life of a man who’s on a quest to disclose and to find the truth. So the narrations are different. Shoah is above my own film, of course, which I can describe as a sort of bridge to Shoah. The reason why he chose not to edit some of the 220 hours of the outtakes is because they did not fit into the architecture of a film. I use his interviews with witnesses, Richard Lazar and Abaham Bomba and others, as if they were characters in order to show how Claude Lanzmann was getting to the truth through the staging of certain scenes. There’s a lot of mise-en-scène in the way he makes the film.

D: One big difference is how Lanzmann appears within these scenes. You see the former train conductor Henryk Gawkowski leaning out—a famous shot from Shoah—but then you see Lanzmann lean out too!

GR: This is a treasure. Yes, the gesture that Gawkowski the train conductor makes means death, beheading, while Claude Lanzmann is somehow making almost a joke—the gesture of a filmmaker at work [when he waves]. The rushes show us a man doing the work of creating a work of cinematic art where the truth happens.

My choices are different, and the films don’t talk about the same thing. Shoah is a film about how death is radical. My film is about how life can be radical. And it’s the life of a man who’s on a quest to disclose and to find the truth.

— Guillaume Ribot

D: Watching your film, I began to wonder if other behind-the-scenes moments were originally part of Shoah too, like when he is walking to and from interviews. Did you think there was a version of Shoah where this surrounding material was part of the film?

GR: I think that Claude Lanzmann didn’t know what Shoah was going to be before he walked into the editing room. That’s why he forced himself to film all sorts of situations and events, but then he chose to keep them out—like the scene where he is dressed up to hide the microphone and wire—because at a certain stage, he thought about explaining how he carried out those interviews. But luckily for me, he decided not to include those things because he must have realized that he had to be radical in showing the subject matter.

D: What insights did Dominique Lanzmann, the director’s wife and a producer of your film, share with you?

GR: Dominique Lanzmann and I talked a lot about her husband Claude, but all these enriching exchanges didn’t directly help me write the text of my film, as I had decided to use only Claude Lanzmann’s own words. Nevertheless, Dominique was, among other things, very important in giving me access to the Shoah film archives. That is to say, absolutely all the documents relating to the historical preparation of the film, the shooting, the transcriptions of all the interviews, and Claude Lanzmann’s notes. In these, I found some very interesting things that I incorporated into my screenplay. For example, I had access to letters written by Claude Lanzmann in which he explained to financiers and witnesses what he wanted to do before starting to shoot Shoah. I’ve also seen his application for an advance on receipts from the Centre National de la Cinématographie, in which he wrote the beginning of a screenplay that was different from that of Shoah. I also had access to insurance documents that might have seemed very anecdotal, but in which I discovered who the crew members were on each shoot and what equipment they used. Thanks to these archives, I was able to immerse myself in the intimacy of a film shoot. This allowed me to deepen my understanding of Claude Lanzmann as a director before the release of Shoah.

D: Obviously, the key choice of the film is that the perspective focuses on Lanzmann—therefore, on the witness. Is this also to show the work required to bear witness, and also to provide an example to others to continue this work?

GR: In my film, Claude Lanzmann says something very important: “Shoah is a race against death. Soon, the living history will have become a dead history. History itself. Shoah is the construction of a memory. And the act of transmitting is all that matters.” That’s what I’ve been trying to do for 27 years, through my photographs, my books and my films. It’s my commitment. A lifetime commitment, I think. Like Claude Lanzmann, I too believe that we must do everything we can to try to pass on what has happened. It’s up to each of us to bear witness as best we can. Historians, the few living witnesses or their descendants, writers, teachers, artists, scriptwriters, journalists, poets and filmmakers. We all have a role to play.

My first Holocaust-themed photography exhibition in 2002 was called “If we stopped thinking about it.” It’s a quote from philosopher Vladimir Jankelevitch’s book L’imprescriptible. This book had a great influence on me and gave me a path to follow: “The countless dead, the massacred, the tortured, the trampled underfoot, the offended are the business of us all. Who would talk about them if we didn’t? Who would even think about it? If we stopped thinking about them, we’d finish exterminating them, and they’d be wiped out for good. The dead depend entirely on our faithfulness.”