In July 2021, Mexican "fixer" Miguel Angel Vega was approached by a European television channel. It was the same type of request he was used to receiving: "We heard this town is really dangerous right now. Can you take us there?"

Behind most big television segments on Mexico’s cartels, there is normally someone like Vega. For a decade, he’s been fielding requests from broadcasters, newspapers and magazines looking to tell definitive stories about Mexico’s war on drugs and organized crime. He takes foreign journalists to where the action is, arranges safe transportation and accommodation, finds sources, translates interviews and makes sure the news outlet that’s contracting him for however many days, or weeks, gets the information they’re looking for. Many in Vega’s line of work are journalists in their own right, working for major television channels and newspapers in their home countries.

But when foreign outlets contact these journalists, the assignments often take a different shape. Vega knows that his profession—known as a "fixer" among journalists—can be dangerous. He’s even written a book about his experiences, living in the liminal space between reporters and organized crime. Danger is part of the job, he says, especially given that his area of expertise is security in Mexico. But the European television channel’s request was one that Vega knew he had to turn down.

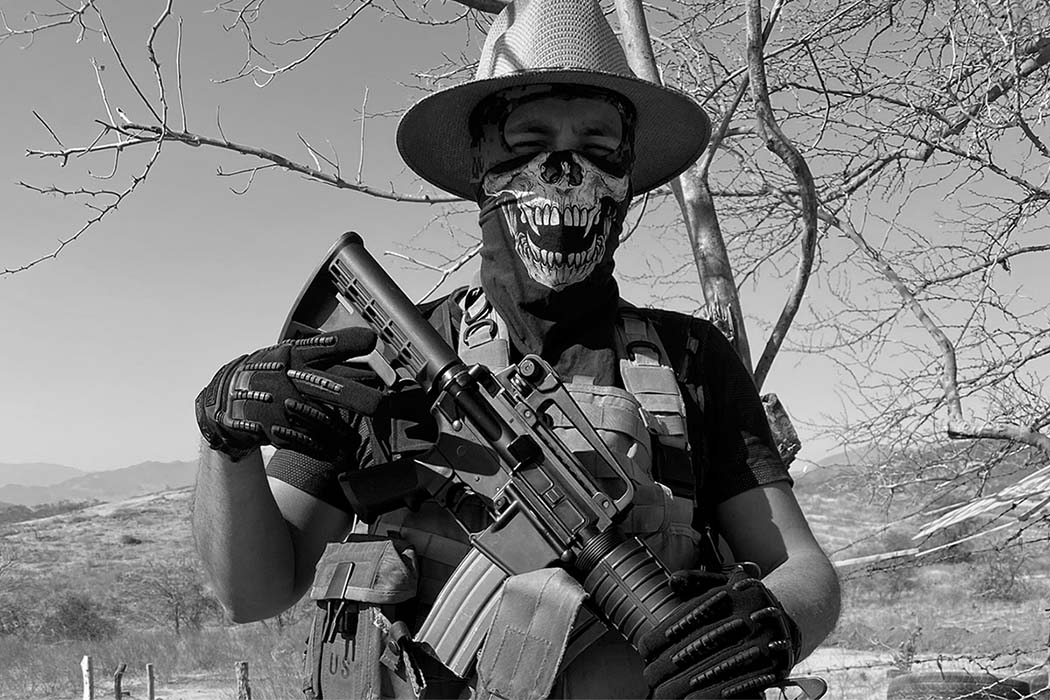

The crew wanted to go to the small town of Buenavista, Michoacán, where one of the leaders of a community policing group had recently been kidnapped by one of Mexico’s most notorious organized crime groups, the Cartel Jalisco Nuevo Generación (CJNG). In response, more than 1,000 members of the community policing group came to Buenavista, with the intention of killing CJNG members. The European producers wanted to go to where the action was taking place, get footage of shots being fired and film dead bodies in the streets.

Vega started as he always does: He found people who knew what the situation was in Buenavista, how to get in and out, and who to talk to. But everyone he spoke to said, "No, I’m not going there, it’s too risky. They’re shooting anything that moves." Vega realized that, with a seven-month old child at home, the assignment was too dangerous.

"When I say war, it's literally a war," Vega explains. "They had drones, they had machine guns, they had Kalashnikovs, they had grenades—you name it." When he told the European producers that he wasn’t going to Buenavista, they asked him if he was a coward. "I’m not a coward, but I’m not stupid,” Vega maintains. “I’m a high-risk fixer, but I’m not a suicide guy."

For many professionals who work as fixers in Latin America, turning down work is a difficult trade-off. Even if an assignment is dangerous, it usually pays well due to being in a foreign currency. But opportunities arise unpredictably, dictated by the news cycle and foreign audiences’ appetites for certain types of stories. The higher payment is compensation for the work being done on a one-off basis, the risks it entails and the punishingly long, fast-paced days. Fixers often find work by word-of-mouth, recommended by someone who has previously worked with them and making it even more difficult to ever say no to work.

For Sofia Villamil, a Colombian fixer and producer, that dynamic adds an extra layer of pressure to an already intense job. Two years ago, Villamil began working a string of high-pressure jobs back-to-back: nine months working on an investigative show about drug traffickers, then straight onto a documentary about Colombian street food, then another documentary on an indigenous tribe in the Colombian jungle. When she finished those jobs, she had "a terrible breakdown."

Villamil has been doing this work for 15 years, but she has never felt like she had enough job security to say no to work in the times that she has been freelance. "I just said yes to everything," she admits. "You jump and jump and jump into projects. I never had time to rest. Never."

That dynamic had begun to take its toll on Villamil’s mental health. A part of the difficulty of remaining in a place where a fixer helps foreign journalists report out dangerous stories, Villamil says, is the lack of security the fixers face afterwards. Her nerves were already frayed by the lack of income stability, but remaining in Bogotá after the investigation into the drug traffickers aired was weighing heavily on her and she feared that she was being followed. She was prescribed medications for anxiety, sleep, and depression. In early 2020, Villamil ended up taking several months off work to recover.

Another thing that weighs on Villamill is the issue of being credited for her work by foreign journalists. In some cases, like Vega’s, fixers prefer to remain anonymous and uncredited for fear that knowledge of their assistance in foreign productions will undermine their own independent investigative work. And while some news outlets like The New York Times are beginning to add "additional reporting" credits for fixers, a report from the Nieman Foundation for Journalism reveals that most foreign correspondents openly admit to not giving bylines to fixers.

"I was trained to basically assume that there's going to be some brown person at the end of the phone who’s just going to do my bidding," says Leah Borromeo, a documentary filmmaker who began her career working for big international news outlets when she was 19 years old, from the Associated Press to Sky News. "It's almost a kind of diminishing title, to say that, 'Oh, I've got a fixer.' And it's like, you're relying almost entirely on this person's knowledge."

And as a woman of color working in the news industry, the "color disparity" that Borromeo saw among her colleagues and the people who got them the sources and scenes they needed made her increasingly uncomfortable—as did the pay disparity, the lack of credit given to established local journalists, and how outlets treated fixers as disposable.

Now working independently, Borromeo prefers to credit local journalists who help her with her work as "location producers." She tries to keep her relationship with them active, rather than disappearing and falling out of touch with them when their work together ends. "Keep checking in," she says. "Keep asking, 'Hey, this was something else that you think we might have missed.' If you can go back there, maybe you can try to engage them again."

Pay disparities and the level of risk that international outlets are willing to expose local fixers to also plays on Borromeo, Villamil and Vega’s minds. Vega recalls being on location with a crew when bullets started flying. The crew pulled out their bulletproof vests, but didn’t provide one for Vega—leaving him to feel like "a thing" rather than a human being. Villamil thinks about the producers she’s worked with who are paid four times as much as they’re willing to pay her, despite her vulnerability to online and physical attacks after a crew leaves. Villamil notes that for foreign outlets, their correspondents’ lives are "more expensive than mine."

Both Villamil and Vega are passionate about their work, which they feel brings important information to wider audiences. But when they found themselves struggling with mental health issues, there were no resources to turn to.

"There is probably some trauma, and there is nobody you can tell. Not even the free press organization in Colombia," says Emmy-winning documentarian Alejandro Bernal. "There is nobody you can say, I don’t know what is happening with me, I don’t know if I should talk to somebody about it."

For Bernal, most fixing requests he gets are for stories about conflict or violence in Colombia in high-risk regions. The risks he’s being asked to take are no longer new; he is older and more experienced than he was when he began his career − and more aware of how dangerous some requests are. But mental health is also a part of the reason he declines this type of work.

Although he recently won an award from the Rory Peck Trust, a UK-based nonprofit that offers resources for freelance journalists covering high-risk work all over the globe, Bernal has never found any similar resources in Colombia. The risks that he once enjoyed taking for the sake of uncovering important truths no longer feel proportionate.

"Personally, I want to leave Colombia," Bernal admits, his voice breaking. "For some years, I really enjoyed that. Nowadays, I’m not feeling comfortable anymore."

Ciara Long is an investigative reporter and audio producer based in the U.S. She was previously a freelance foreign correspondent in Brazil, where she wrote for Foreign Policy, The New York Times and World Politics Review.