During the past fifty years, television channels, continually expanding online options, even theatrical cinemas have made short-form and long-form documentaries available to an ever-broadening audience. So many documentary films of so many kinds are now available, that it’s easy to be unaware of accomplished filmmakers who have made and continue to make remarkable documentaries and who also take pride in contributing to their colleagues’ work. Robb Moss is one of these filmmakers.

Moss is a pioneer of what we now call “personal documentary,” specifically, a certain set of approaches to filming personal life that have emerged in Cambridge, Massachusetts, largely via the interplay of the Film Section at MIT and the Visual and Environmental Studies Department (now the Department of Art, Film, and Visual Studies) at Harvard. Moss earned his MS degree at MIT, under the tutelage of Ed Pincus (Pincus’s Diaries 1971-1976 [1980] is a canonical personal documentary), and has taught at Harvard since 1983, along with fellow personal documentary pioneers Ross McElwee and Alfred Guzzetti.

Moss has made fifteen-plus films of various lengths, including Riverdogs (1982), about a group of river-guide friends rafting through the Grand Canyon in 1978, which he considers his first real film; and The Tourist (1991), a feature focusing on his world-travels as a freelance filmmaker and on his and his wife’s struggle to have a child, narrated in the first-person mode made familiar by Ross McElwee (Backyard, 1984; Sherman’s March, 1986). Moss and Peter Galison, professor of Physics and the History of Science at Harvard, have collaborated on two features: Secrecy (2008), which focuses on the dangers of governmental secrecy; and Containment (2015), about containing nuclear materials now and for the next 10,000 years.

But Moss’s most remarkable work is his trilogy of “river films,” beginning with the idyll, Riverdogs, and continuing with The Same River Twice (2003), a feature during which several of Moss’s friends and Moss himself revisit Riverdogs, from their now-middle-aged perspective.

His new feature, The Bend in the River (2025), is a culmination and likely completion of the project that has been Moss’s primary filmmaking focus for more than forty years. The Bend in the River explores the earlier river films, from a continuing present, twenty-plus years after The Same River Twice. Together, the three films are as intimate and thoughtful an evocation of the process of aging as can be found in modern cinema—and in many ways the absolute antithesis of reality television.

In his teaching at Harvard, Moss has mentored a generation of accomplished filmmakers, the best-known of whom are Joshua Oppenheimer and Damien Chazelle. From 2004 until 2022, he was a regular mentor for the Sundance documentary labs in Park City, Utah, where he worked collaboratively with documentary editors and directors and contributed to many films.

I had previously interviewed Moss about his filmmaking through The Same River Twice, for A Critical Cinema 5 (University of California Press, 2008), and I focus on his career in Chapter 7 of American Ethnographic Film and Personal Documentary: The Cambridge Turn (California, 2013). We spoke on Zoom about The Bend in the River in June 2025; our conversation was expanded during the following weeks before its premiere at Telluride this weekend, and has now been edited for length and clarity for Documentary.

DOCUMENTARY: When you finished The Same River Twice, were you, and/or the friends featured in the film, already thinking about a third river film?

ROBB MOSS: When The Same River Twice was premiering at Sundance in 2003, the question of a next film came up instantly with audiences after screenings. They’d say, “How about calling it ‘The Same River Thrice?’” to which I’d respond, “How about ‘The Naked and the Dead?’” Those titles have been suggested over and over. But to answer the question, a third film was on my mind. And then the question was: when could that begin to happen?

The first shoot for what has become The Bend in the River didn’t begin until 2016, during a river trip on the main fork of the Salmon River [in Idaho], and even at that point it seemed a little too early. I was 66 and hadn’t quite felt my aging in a way that could be interesting. At the same time, it seemed like hubris to wait any longer, unwise to be too careful. So I began filming, and discovered during the first two years of shooting that it was really complicated to film aging.

Filming is easier when you’re young and naked in the Grand Canyon or when you’re hip-deep in middle age, living with the life choices you didn’t quite know you were making. By middle age, your choices are inscribed in every step you take, something the camera can see, even if we cannot.

Becoming elderly is different, more internal. Of course, there are the external factors, the wrinkling and all of that, but those are the least interesting parts of getting old. And too obvious. It was harder to understand what the internal stuff of aging actually is. Deciding how to best film that took a long time.

D: You’ve talked about how filming is your way of keeping in touch with your friends. I’ve been very bad at staying in touch with people myself. You seem to have found a way to stay in touch for life.

RM: Keeping in touch wasn’t so much a way to stay friends, though it did help since we saw each other more than we probably would have otherwise. In my own middle age, having children and other work, it was harder to visit people. But by including my friends in my filming, I knew that though I might be making the most awful movie, at least I’d see my friends!

D: During the time between Riverdogs and The Same River Twice, how often were you filming?

RM: I filmed over six years and edited over three. I filmed things that, as they came up, struck me as maybe important. I filmed an election that Jeff Golden was in. He cared—still cares, deeply—about being a public servant and has continually wanted to serve in elected office. While he had won and lost previous campaigns, he also continued on as a writer of political novels and worked as a radio and television talk-show host. I filmed Barry Wasserman retiring. And I filmed a stray river trip here and there, with people who were on that first trip. I also filmed their daily lives over those six years.

Of those who have been in all three films, Danny Silver was the least interested in being filmed. Everybody else was, or at least seemed, pretty comfortable with me and the camera. Danny didn’t like it, funny because she’s the most theatrical of us all—a performer, a singer, a dancer. She loves doing all that, but somehow, the documentary camera creates for her a strange vibration that she didn’t like, at least early on.

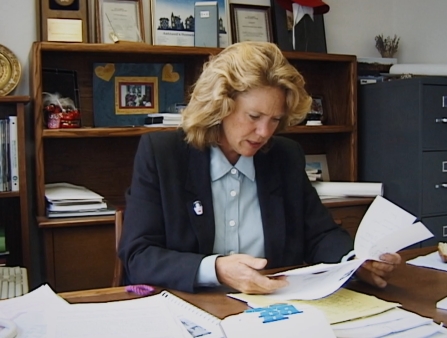

I grew up with Danny—I met her when I was 12 years old. I met Jeff when I was 11, and Barry when I was 15. They were long-time friends before I began river running or filmmaking. I met Cathy Shaw on the river when I was 25; she and Jeff were a couple then, and married later. Over time, Cathy discovered she too had a talent for politics, serving as the first woman mayor of Ashland, Oregon, and writing successful books about how to run campaigns. I met Jim Tichenor in 1975 while employed by a rafting company in California. We worked together and became friends. Jim is one of the most extraordinary people I’ve ever met and almost impossible to describe.

Cathy Shaw in Riverdogs.

Shaw as mayor of Ashland, Oregon (she served three terms between 1989 to 2000) in The Same River Twice.

Shaw in The Bend in the River.

D: After seeing a rough cut of The Bend in the River, my students and I talked about how it must have been a conundrum to keep the third river film from seeming like a rehash of the second.

RM: I was totally anxious about that. I’ve hoped that each film would make sense of what life seems like from within a particular time frame. Riverdogs, a single river trip shot in 1978, stood for the extravagance of youth. Shooting for more than four years while making The Same River Twice, and six years for The Bend in the River, I attempted to place each of the characters into the flow of their lives. The film means to put their youth, middle age, and impending old age into something like dialogue. Not surprisingly, perhaps, these lived moments are quite different from each other.

What does this actual aging feel like? How is the past regarded? What’s the conversation between one’s young self, one’s middle-aged self, and one’s elderly self? The Bend in the River required an entirely different editing scheme from the earlier films, one that Jeff Malmberg, the film’s editor, did an absolutely magnificent job with. Jeff understood that all these pieces of time had to ricochet off each other in a way that wasn’t just a straightforward narrative from then until now, even though the arc of the three films is from then until now—because it’s an illusion to think that the past simply leads to the present. The meanings of our lives are constantly in flux, and the internal workings of Bend, like our own lives, move back and forth as we think about things and as things change and take on new meanings. Over time, nothing stays put.

In Same River, Barry learns he has cancer and is on the phone, actually with Jeff, telling the story about how he found out. Then, in a quieter voice, he says, “I didn’t tell my kids and I haven’t told my mother—the people who care the most but can least deal with it, I wanted to protect.” Then, twenty years later, in Bend, on his 70th birthday, Barry’s looking at that scene from The Same River Twice and is moved and relieved that he didn’t die. He’s just received a note from his daughter, Hannah, who was at the birthday party, saying how glad she was to have been there, but also, “I’m really not happy you have birthdays because you’re supposed to live forever.” Barry writes back to say how much he loves her, and that he’ll stay alive as long as he can, but not forever. When he was a middle-aged guy, he felt the need to protect his young children from his mortality, but as an older person, he feels he needs to prepare Hannah that he won’t always be around.

There’s another scene with Barry where he’s telling the story of how Teague, his youngest child, was conceived. He and Deborah had seen a film that they found so moving that Barry wrote love poems to Deborah. They subsequently went to bed and conceived their daughter. We see Teague as a toddler in that scene, then the film cuts to twenty years later. In the blink of an eye, Teague goes from baby to thriving twenty-year-old woman rowing on a river with her father, who is years into his subsequent marriage.

This seemingly sudden jump through time mirrors my experience with my own children, but a friend whose child is quite ill saw Bend; he hoped that his child would live to be as old as Teague. The mortal strands that hold everything together are seen differently depending on where you are in your own life. Aging surfaces that recognition like crazy.

D: When I’ve shown The Same River Twice, my students have generally felt that your protagonists, who looked so wonderful in Riverdogs and seemed to be having such a great life, were, in middle age, a disappointment. Of course, they thought this way, not knowing what those young river guides’ lives were actually like—when you were shooting Riverdogs; your relationship with your girlfriend was fraying and you were struggling to film. When I decided to show my class The Bend in the River, I couldn’t help but wonder…

RM: …how were they going to relate to it!

D: Yes. A film about elderly people? Yuck. Just the other day I found out that two people I’d known for decades had died. I’ll go to memorial events for them this week. Those events are more and more a part of my aging, and I think that young people think this is what aging is. But there’s the other part: I’m having a blast! It’s really fun being old, and I think Bend demonstrates that. Even Jim, who younger folks might say is something of a “failure”—he never finished his house!—seems good with where both he, and his house, are. And Jim provides The Bend in the River with a crucial metaphor.

RM: “Perfectly half-finished.”

D: Perfectly half-finished. It’s the same with the weird stances Jim takes during the film; he looks all a-kilter, but in fact he seems in perfect balance, at least for him. For the students to see that going from middle age to being elderly can also be fun, maybe even exciting, is unusual for a film that doesn’t fall into a corny Capra-esque mood. I was surprised by how excited my students were about The Bend in the River.

RM: When I made The Same River Twice, I assumed it was for middle-aged people; I didn’t know if young people would be able to relate. Younger people seemed to like Riverdogs, where the characters don’t seem to know that they’re naked. They’re still in the Garden, and haven’t yet taken a bite of the apple of their adulthood. The question in The Same River Twice is: what’s it like to move out of the Garden and into the temporal world? Which is, of course, one of the major questions of Western thought.

One of the things that you see in The Bend in the River is that you don’t have to stop being yourself to get old. Young people sometimes ask me if it hurts to get old. When I was a young person, I imagined that getting old meant that I was going to become somebody else, someone less alive. It turns out that I didn’t lose myself. I found I could keep my friends around me and keep my youthful appetites and pleasures alive. I hope it’s a relief for young people to understand that possibility.

D: There’s also the moment when we realize that Cathy is running Jeff’s campaign; after The Same River Twice, who could have imagined that! And there’s the moment when Jeff and Cathy have discovered that some of what Jeff says in Same River is now a political problem and are battling over how to deal with this situation—while Jeff’s new wife is sitting in the background having lunch, watching them. That suggests possible aspects of getting older that the students (and maybe many middle-aged folks too) have probably not imagined.

RM: Absolutely. Making this movie has made me think about coincidences. What is the role of coincidences in narrative? Why do we love them so much? What is it about them that’s so appealing?

About that scene—Jeff picked me up that day at the Medford airport in southern Oregon, and as I’m sitting in the car, filming, he gets the text! Luckily, my camera was already turned on. When you’re shooting, you never know exactly when to begin to shoot. If you wait until the event is happening, you’re always a beat too late and can miss the context for what you’ve shot. On the other hand, if you keep the camera running, you’re shooting too much. So Jeff gets the text: “Oh,” he says, “It’s about The Same River Twice!” and it’s quickly clear that Jeff’s rivals are trying to use what he says about his adultery in my film, against him! My heart sinks.

D: I remember you saying, in The Tourist, “It is often the case that the worse things get for the people you are filming, the better it is for the film you are making”!

RM: Nonfiction filmmakers always have to contend with this contradiction, that difficulty makes for a more compelling film, even as lives can be upended. But I couldn’t have designed this moment any better for The Bend in the River, and how weird is that?

Bend was full of temporal challenges. Can we move through time in ways that are comprehensible without titles or voice-over? And there’s very little continuity from scene to scene. People are older, younger, have different hairstyles, hair colors. In fiction films there’s usually a person keeping continuity, making sure that everything is continuous. For Bend we struggled to make the scenes careen off of each other in ways that were legible, but not overly proscriptive. I hope we’ve been successful.

D: Did you all realize how much the Grand Canyon had changed before you did the river trip we see in Bend? The change is pretty shocking.

RM: Well, we were all aware that the river was losing water, but I don’t think we knew how much and how quickly. I’d been reading articles about what was happening to the river and I remember thinking that the Colorado was running out of water as we were running out of time. But it was shocking to see…

D: In recent decades you’ve done a lot of work with Sundance—are you still working with them?

RM: Not since 2022. It was incredibly fortunate for me that Diane Weyermann came to Sundance in 2001 to run the documentary program.

The Same River Twice was at Sundance in 2003 and I was on the jury at Sundance the next year. Diane asked if I would be part of their first documentary edit lab and I went there often from 2004 to 2022—around a dozen times. The Sundance lab experience meant that I had the rare opportunity of seeing four or five really interesting films-in-progress from around the world, curated by Sundance. These films, some made by established filmmakers and others by promising young filmmakers, were often really good—though it was clear they could be better than good. The assumption was that by working with four editors and two directors at the editing table, the filmmaker would enhance what was already there. The whole role of editing in documentary, the relationship between editor and director, is profoundly important and Diane’s awareness of that was the soul of the lab.

Working with all these people was important for me. As a director, you shoot whatever few films you can, over a lifetime. Our world as directors is actually sort of narrow, though sometimes we do meet each other at festivals. Being part of Sundance massively escalated my awareness of the national and international documentary film community, and created lifelong friendships around our love of film and our intimacy in thinking about interesting ideas that aren’t quite formed.

I was not one of the lab editors, who were the stars of the labs. I was one of the directors. But before I started working with Karen Schmeer on The Same River Twice, I’d always edited my own stuff. I love editing. I just ran out of time—you know, teaching, three kids, full-time filmmaking… It was hard to give editing up, but also great to give it up. Working with Karen, with Chyld King on Secrecy and Containment and with Jeff Malmberg on The Bend in the River, taught me a lot about filmmaking. A wonderful editor and person, Karen was struck by a car and died in 2010. Her friends and colleagues continue to mourn her.

D: Somebody once told me that in some years, you’re thanked in all the Oscar-nominated documentaries. How much of an exaggeration is that?

RM: Well, back in 2014, three of the five nominees were former students, and there was a period when I worked on Yance Ford’s 2018 Strong Island, RaMell Ross’s 2019 Hale County This Morning, This Evening, and Steve Bognar and Julia Reichert’s 2020 American Factory, all nominated for Best Documentary. Former student nominees include Joshua Oppenheimer (The Act of Killing), Jehane Noujaim (The Square), Rick Rowley (Dirty Wars), Amanda Micheli (La Corona), and Damien Chazelle (Whiplash and La La Land—I was Damien’s thesis advisor when he started Guy and Madeline on a Park Bench, the precursor perhaps to La La Land).

Many accomplished filmmakers have come through our Harvard program, and I’ve been fortunate to be part of their early lives, and sometimes beyond that—some will stay in touch and I’ll look at cuts of films. Lauren Greenfield has sent me many films over the years and recently directed the 2024 TV series, Social Studies, for FX.

But while winning awards is great and I am happy for my former students to receive such public acknowledgment for their achievements, for me the pleasure derives from how good their films are, how worked on, how hard-fought.

D: The dozens of films you worked with during the Sundance years included your Cambridge mentor Ed Pincus’s project, “The Elephant in the Room,” which became One Cut, One Life (2014), his last film.

RM: One Cut, One Life was made by Ed and Lucia Small. Mary Kerr at LEF was a producer. I worked on the film with them, driving to Vermont to look at cuts, and to see Ed before he died. Lucia died in 2022.

D: The credits for the film include Frances McDormand and Joel Coen as executive producers. What was their role?

RM: My partner, my girlfriend, Davia Nelson (who is one half of NPR’s The Kitchen Sisters) has been friends with them for many years, and during the time I’ve spent with Davia (who was my girlfriend while I was shooting Riverdogs!), I met them. Joel and Fran had seen The Same River Twice when it was at New York’s Film Forum in 2003. And at first, we had conversations as filmmakers. Over time we’ve become friends. They saw cuts of Bend along the way and were a touchstone for me. It took me a long time to feel comfortable asking if I could list them in the credits, and when I did, they were gracious enough to agree.

D: You use visual text very sparing in Bend in the River—near the beginning, text provides context for Jim diving into the Colorado to begin the film. Then just beyond the midpoint, there’s one somewhat mordant couplet:

We thought we were immortal

and the river was eternal.

At this point, is another river film even imaginable? What comes next?

RM: Filming my friends when they were young and naked, I was just a speck in the landscape. Riverdogs was my first real film, so keeping the camera safe and figuring things out felt demanding and complicated. If anything, the others just felt sorry for me. They were having a great time on a 35-day river trip and I was tripping over wires and cursing.

Twenty years later, for what would become The Same River Twice, I’d show up with this dinky, really dinky, standard definition video camera and film my friends doing things like making peanut butter and jelly sandwiches for the kids to go to school. I’d come back year after year; they were glad I was there, even with a camera, and I had a wonderful opportunity to watch and record my friends’ lives, mostly as if I weren’t there. But at no point did they think they were going to be in a movie.

When they came to Park City for the premiere of The Same River Twice (I did show them the film in their homes first), they saw themselves as part of this big film festival, and it was, “Oh My God—I’m so exposed in every sort of way!” Barry had fun with it. People would see the film, then recognize him on the street and say something nice. And Barry would thank them. Then finally someone said, “You were really good in the film,” and Barry responded, “Well, I’m glad to hear you say that because originally Robb wanted me to play Jim!”

The Bend in the River was different. This time, they all totally knew, as I was filming them, that they were going to be in a movie. So at the beginning, the shooting was much more self-conscious. But, over time, friendship trumps self-consciousness; if you can be there long enough, you can wait that out. Danny finally came back to allow herself to be filmed, which was generous and huge because the film wouldn’t be the same without her. She provides such a powerful life force and demonstrates still another way of getting older, one that’s particularly hers, but resonates and is a model for us all. Anyway, it was a whole different process to film The Bend in the River, for me and for my friends.

As to what comes next, I’m trying to stay alive as long as I can and find out.

The Bend in the River.