Courtesy of Sundance Institute

To Catch a Predator (2004–2007), a periodic segment on the TV newsmagazine Dateline NBC, was one of the biggest nonfiction sensations of the 2000s. The show collaborated with various local law enforcement agencies around the U.S. to entrap would-be child predators, having decoys posing as minors speak with them online and luring them to houses for promised sexual encounters, where the cameras and police would be waiting for them instead. Host Chris Hansen would greet each target and briefly interview them before officers swooped in.

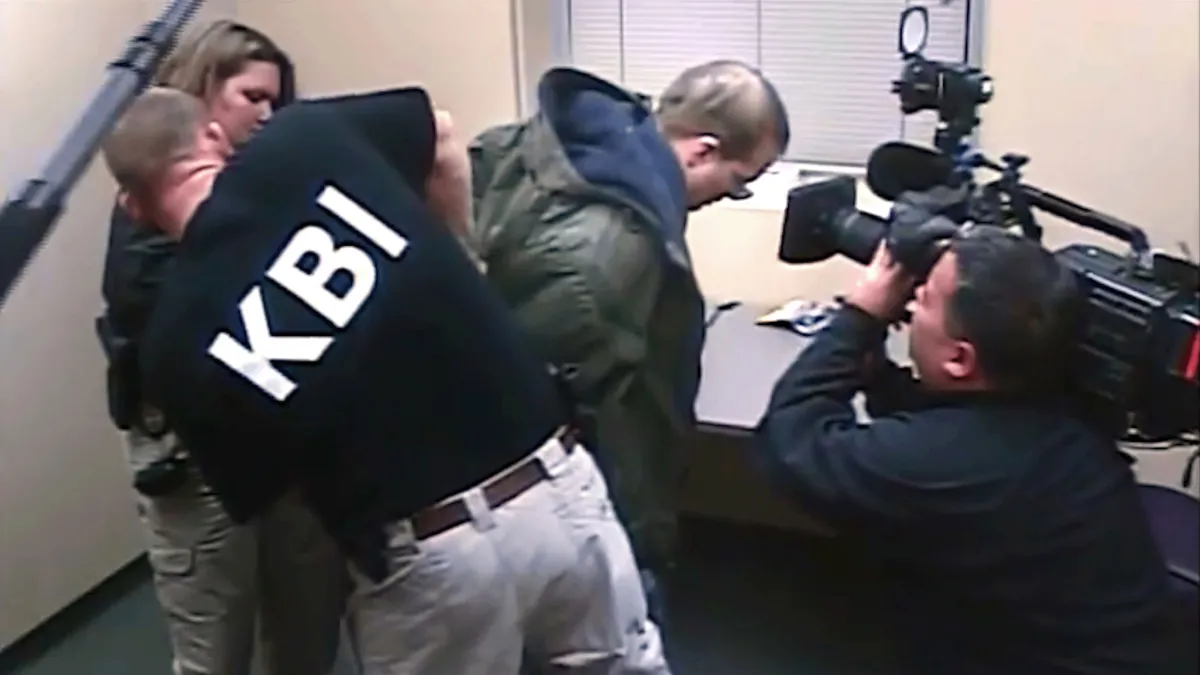

The show made popular entertainment out of disturbing material, and drew great viewership, myriad pop culture references, and sharp criticism during its run. It received particular fire after one 2006 incident in Texas, when a target didn’t show up for a sting, and the TV crew compelled police to go directly to his house, spurring him to shoot himself. The new documentary Predators, recently premiered at the Sundance Film Festival, examines this and other ethical issues around the program. In particular, the film scrutinizes the host of copycat media operations that have arisen over the years, as well as the show’s broader influence on the true crime genre.

Ahead of the premiere, we sat down with director David Osit over Zoom to discuss To Catch a Predator and its modern fan community, finding all the materials used in Predators, and the delicate balancing act involved in incorporating so much raw footage. This conversation has been edited and condensed for time and clarity.

DOCUMENTARY: You delve into your youthful interest in To Catch a Predator in the film. What resurfaced that interest and made you think it’d be a good subject for a documentary?

DAVID OSIT: For a while, I didn’t think it would be good material for a film. I knew the show, obviously, and I heard about what happened in Texas years later, but I never thought there would be more to it than a typical salacious true crime story, which wouldn’t have interested me.

But then, on a random internet search (as we’re all wont to do), I found the show’s online fan community, which is small but very passionate, on Reddit and their own forums they’ve maintained for the better part of two decades. They’d been collecting raw footage from the show—interrogation videos, phone calls with decoys, all sorts of things. Watching this material that never aired, or which only aired in an edited form, was the hook for me. There was such a deeper emotional experience. I’d see some of these men and feel bad for them, which never happened with the show.

The raw footage gives us room to meditate on what we’re looking at, to contemplate it. Contemplation is not part of the language of true crime or reality TV. I could watch this material, then go watch a clip from the show or read a chat log and be disgusted at what these men had done, then listen to a phone call between them and a decoy and feel bad for them again. There was this emotional ping-pong in my head and heart. I wondered what it would be like to make a film with that experience as its spine.

D: Where does all this footage online come from? Are there any legal issues around using it, or does it all fall under fair use? How much searching did you have to do to find material like the footage of what happened in Texas?

DO: Yeah, it’s all fair use. A lot of those clips come from FOIA requests fans made. Some were leaked from depositions that were part of lawsuits against the show or defense cases for people arrested on the show. NBC also put out some of its own “raw” tapes. And Perverted-Justice—the group NBC originally hired to do the stings—released phone calls between decoys and targets. There were a bunch of different ways this material could get out into the world, and it’s all been collected into an online archive on YouTube and Google Drive over the last 20 years.

I had to dig around a bit harder to find someone in possession of the Texas footage. Watching that material compounded those feelings I discussed earlier even more—seeing the cavalier way police were functioning in conjunction with this television program, all the weirdness around it and the performative nature of it, watching that unfold in raw footage with multiple camera angles. There’s a moment when the cameraperson is getting artistic B-roll of police tape, and it hits you that the tape is up in the first place because of what the TV crew was doing.

Watching the edited episode about that incident had its own fascination to me because of how different it was from watching the raw material. Again, it goes back to being allowed to contemplate. You can place yourself in this moment when you’re watching raw footage. As an editor, I think about that, especially since I’ve often worked on projects adjacent to true crime. There’s a quote from Coppola that a film’s never as good as its rushes and never as bad as its first rough cut. Raw archival material makes your brain travel in 10,000 different theoretical directions, and then it’s edited down, typically to say just one thing—especially on shows like this, which are designed to flatten people’s emotional experience.

D: Were any extant true crime projects useful for guiding your thinking in how you approached this—whether as positive or negative examples?

DO: It’s more just being in the periphery, and our industry being in the periphery of true crime—and lately being in the shadow of true crime. When I was first interested in nonfiction filmmaking, The Thin Blue Line was the one [true crime title] I knew of, and now there’s more of it than ever before. I could use the genre a bit, but I felt I could do it differently.

There’s a version of this movie where the audience is reaffirmed at every turn that they’re the good guys because they consumed this story about how there are bad people out there. I was more interested in removing this idea of good and bad, that power structure true crime is based on. Usually the good guys are the police and the bad guys are the criminals, and there’s no room for interrogation. I’m not trying to flip the script; I’m just trying to present something more about the human experience. All of us—predators, prey, consumers, creators—are complicit in telling these narratives. Narratives are very powerful. It’s what religions are based on.

D: Considering framing and complicity on multiple levels, how do you balance presenting this material with not being exploitative of the people in it? This is something you openly discuss in the film, of course.

DO: I was always trying to think about my goal and what I was trying to show the audience. I felt this way a lot with Mayor (2020), too. The typical Western representation of the West Bank is reduced to flatness and violence and suffering and victimhood. I wanted to offer a different image. I felt the same with this film.

For example, in the very long sequence about the Texas incident, there’s a world where I put score underneath it, where I could dramatize it. But I wanted to always make sure the audience was left to find their own path forward emotionally with what they were seeing. That’s not to say I wasn’t editorializing; it would be silly to suggest there was no authorship to this. But I felt I had a responsibility to use the form of my film to say there’s a different way to look at this material which was once turned into entertainment.

D: The film is divided into three acts: the first about the show itself, the second about its influence, and the third following Chris Hansen and what he’s up to now. Did you always have that structure in mind, or did you arrive at it through the edit?

DO: I knew we’d get into these three nodal ideas, that we’d make a conceptual moonshot and then have a place for the space shuttle to come back to. “What happened with the show? What’s happened since the show? What world has the show helped create?” Asking those questions created the pockets of what the content would be.

I was editing throughout for about 13 months, and I worked with four other editors at different times. The first one, a dear friend and a wonderful editor named Erin Casper, I just gave her one storyline. I didn’t tell her where it would go in the film. I said, “Cut this one part like a true crime movie.” And I got to see the material in a different way. Then I took that same material and gave it to a different editor later on in the process, and I said, “Let’s cut this the same way everything else in the film is cut.” That let me see how the footage was able to speak. There was a lot of experimentation and thrown-out ideas. In the service of exploring those nodal questions, I saw the story evolve the more time I spent in the edit room.

D: Each of these three nodes also comes with a different predominant formal approach. The first act is mostly archival, the second has you embedded with a modern predator hunter YouTuber, and the third is based heavily on interviews.

DO: It’s something I hoped would work from early on. There were many points in the editing process when I would say, “Oh, okay, this is it. The structure’s now there.” I wrote out the idea of the structure well before I shot 85% of what you see in the movie, and then I tried to model it out. And then I’d watch it, and there’d be occasional moments where I thought it was hollow, where I wasn’t yet feeling what this person was saying or not understanding things differently. I had to accommodate the audience’s experience, not just my own. That meant times when I had to slow down and times when I had to pick up speed.

D: That emphasis on slowing down seems key. To Catch a Predator condenses each story into however long the segment has at the end of each episode of Dateline. And here you see what happens if you decompress and are forced to sit longer with this material. When editing, how do you figure out how long to let things play out?

DO: That’s the funny balancing act. With this film, it relied on many trusted eyes watching things back, and working with two of the greatest producers I could imagine, Jamie Gonçalves and Kellen Quinn. We had to be aware of where a viewer may zone out, where watching the raw footage starts to feel too much like watching raw footage. It’s a fine line that required a lot of nuance.

I had access to hundreds of hours of interviews and interrogation videos. Sometimes I realized I should try a different clip to make one moment work, because something about the tonality or texture of what I had was making things move too slowly or keeping the audience at arm’s length. It required some gymnastics, but it was actually my favorite part of the edit, interrogating the idea of rawness and strategically placing that material against edited material and seeing how that feels.

D: Your interviews with Hansen are the backbone of the last act. How easy was it to get access to him? Was his participation ever in question?

DO: I emailed him and he wrote back saying he’d love to participate, and then we went from there. I’m loath to discuss the final interview too much because I’m so proud of the way it’s built and structured, and it’s very much what the whole film is leading up to. What I will say is that I felt like I couldn’t make the film without talking to him.

I wanted to know how he saw himself in the canon of true crime, because he has a very different view of it, coming from journalism. There’s a lineage between journalism and true crime, and shows like To Catch a Predator are the missing links. There was Cops, of course, but reality shows are a very different kind of animal. This was part of Dateline. It felt important to unpack that with him.

As you see in the film, there are people who do this work because they think it’s the right thing, these social media vigilantes, and there are people who have made it their career. And then there are those in the middle, like Chris. And that’s also true of a lot of documentary filmmakers. Everyone believes they’re on the right side, but we also make a living doing this work. That middle ground became curious to me, and I had a lot of questions not just about what Chris does, but about what I and my colleagues do for a living. There’s this middle space, and you don’t know how far you are on either side.

Dan Schindel is a freelance critic and full-time copy editor living in Brooklyn. He has previously worked as the associate editor for documentary at Hyperallergic.