Editor's note: What follows is an edited version of filmmaker Zeng Jinyan's keynote address at the 2020 Getting Real Documentary Conference. To watch the full keynote, head to https://www.documentary.org/video/zeng-jinyan-keynote-face-working-women

I am here to provide a China perspective and a feminist point of view, raising some questions about the face of working women, and rather than addressing what we are concerned about as filmmakers, distributors and human beings in a COVID 19 pandemic and politically chaotic era.

The Authentic Self as Method: Trauma, Memory and Resistance

When I say a China perspective, I mean the view of someone who was born and raised in mainland China but has lived the past eight years mostly in Hong Kong, the US and Israel. My PhD and post-doc studies and art work over the past decade are all about culture and politics; intellectual identity and social activism; poetry and documentary film; gender and sexuality; and ethnicity, with a particular emphasis on China. I was born in southern China as a Hakka—meaning, the guest of the place. We were initially seen as strangers in our hometown. It is like a metaphor of my life—always being a stranger, eccentric to society and those in power. I lived under around-the-clock surveillance, periodic house arrest, and forced disappearance from 2004 to 2012 in Beijing, as part of the political consequence of my civil society work and my then marital relationship with a noted rights activist in China. My daughter was born and raised under house arrest.

I recently realized that over the past decade, I had been avoiding recalling these experiences. Somehow, I was in a living mode of bad faith—meaning I was wanting to cut off my connection with my own painful memory and past; I was terrified by my status of being rejected from any job in my own Chinese culture, due to the state’s direct intervention into my job status—also because people around me were too afraid of my history and its political impact on them if they were associated with me. Furthermore, many liberal intellectuals and conservative scholars distance themselves from my feminist perspective, which could adversely impact to their careers and lives. It is not merely somebody’s fault. It is a mechanism of relational repression backed by the government’s coercive power, which interplays with patriarchal power in Chinese society. It is also common in many authoritarian contexts. Furthermore, many liberal intellectuals and conservative scholars distance themselves from my feminist perspective, which could adversely impact to their careers and lives. I was desperate for the opportunity to find a job; I even would not mind denying my “authentic” self, per Martin Heidegger. I was trying to forget what had happened to me and my family over the past two decades in order to be an ordinary nobody. I might have successfully cut off almost all social connections so that I would bring no harm to other people under China’s relational repression practice. But I cannot do this anymore.

Though I’m trying to forget the past and be anonymous, I have to deal with this trauma and the psychological impact, so I made three documentary films to regain the ability to be a human.

Prisoners in Freedom City, made in 2007, was shot by my ex-partner Hu Jia while we were under house arrest. The footage is from the eye of a prisoner and from the limited angles of the windows from the house. No matter where you go and what you do, you were being watched, with eight strong men physically present within visible distance. Nowadays, isolation and digital surveillance have become a reality in many people’s daily lives. How can a person be oneself while living under isolation and around-the-clock surveillance? How do you resist and make life liveable for yourself?

Documentation of my experience is my first step of resistance. I don’t have a university degree or any professional training in filmmaking. I was inspired by Waiting for Godot to make this documentary, using the repeating of daily surveillance scenes to provoke viewers and to question who are the prisoners of this form of imprisonment. Was it us? Was it the police? Was it the humans in the system?

A Poem to Liu Xia, which I made in 2013 with Irish filmmaker Trish McAdam, addresses the question, How does one reclaim one’s self from living under the shadow of another person—often an intimate partner? How does one deal with the erasing of one’s name on a daily basis due to a gender-biased culture that only sees a woman as the wife, the appendages of a man? This is practiced and reinforced by various stakeholders, including media and international organizations, who do not have the awareness of recognising a woman’s existence and independent identity. I wrote the script and did the cinematography for A Poem to Liu Xia to tell a story about Liu Xia. She is, first of all, a forbidden artist (poet, photographer and painter) in China, not only the wife of Nobel Peace Prize laureate Liu Xiaobo. All photographs in the video were taken by Liu Xia and in this way, Liu Xia speaks for herself, even though she was under house arrest at that time.

Women as Method: Gendering Social Action and Filmmaking

Outcry and Whisper, which I made with director Wen Hai and Trish McAdam, premiered last April at the 51st Visions du Reel in Switzerland. For this film, I wanted to make a conclusion about my own story and investigate how political, economy, gender and cultural power interplay in suppressing women and how women act beyond social activism and ideological frameworks to gain individual and collective autonomy.

In the society where I am from, women, like many other minorities in terms of social categories, have to be dissidents before becoming women. In the United States context, on the one hand, we see individual/collective and diverse voices with intersectional perspectives; on the other hand, what’s going on in the US might inspire the public to better understand the need to be a dissident. In the Chinese and broader Asian contexts, dominant political ideology intertwines with gendered power; the mainstream political, social and cultural discourses are gendered, for these discourses are mostly produced by men, and by the relatively dominant (not partnership) frameworks. This framework is commonly seen in many other cultures.

I would like to share a story about Professor Ai Xiaming. She is feminist, independent filmmaker and retired literature professor. When I assisted Ai Xiaoming’s production and distribution of her film Jiabiangou Elegy (2017), a video testimony of labor camp survivors, she found that some of the protagonists were aware that they didn’t have the language to describe what they or their families had experienced in the labor camp during the Anti-Rightist movement in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Some simply adopted the official ideology and language to describe the labor camp as “a mistake that has been corrected.” However, the labor camp history is still not allowed to be openly commemorated, discussed or written about in teaching materials. As a scholar and filmmaker, she is searching for a language to recall history, and also searching for a new film language to present the complexity and inhumanity among labor camp inmates. In the end, it is only possible to tell the labor camp story from a feminist epistemology: We usinge micro, personal narrative to relate lived experience, with the intention of deconstructing the impact of ideological narrative from the government. We would like to hear the voice of the “victim/survivor,” meanwhile arguable perpetrator under the extreme labor camp surviving conditions, to get us “uneducated” by the knowledge produced through the official framework, and mainstream framework in global and local societies.

This method, in my perspective, also helps to deal with another threat, namely the globalization ideology faced by Chinese filmmakers, and probably all of you. That is the single logic of rule in film funding, filmmaking and distribution. It refers to what Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri have said in the book Empire in discussing globalization: “Sovereignty has taken a new form, composed of a series of national and supranational organisms united under a single logic of rule.” Even in the so-called independent filmmaking and distribution world, we still see words like “award-winning, excellent, outstanding, successful, change, mainstreaming its market, etc.” I have never participated in a pitch because I am afraid that I cannot prove that I will be successful, or produce a film to meet established expectations. I doubt if I can say something to prove that I will be “successful,” for then I will pay the price by not being able to write poetry and make films anymore. To me, writing and filmmaking is about discovering uncertainties and provoking readers and viewers, in a responsible but unlimited way.

In the independent filmmaking sphere, most of what I have learned and created is from pain, failure, discomfort and tension. Locality, intimacy and vulnerability are often at the center of these stories, where I see human dignity and social reality. The social reality we face is that poverty, inequality or violence are the major issues in most grassroots people’s daily life experiences. I believe this is the core value of independent filmmaking and distribution. Independent film, to me, is speaking truth to power, in all kinds of social contexts, not only in its content but also in its cinematic language. Especially in times like this when we have to live with the COVID-19 pandemic, it is a time for us—filmmakers, funders and distributors—to rethink the problem of globalization and independent filmmaking, to further value locality and diversity while building up solidarity across geography, gender, race, class and other borders.

Let me return to Outcry and Whisper as an example of filmmaking with feminist epistemology. Like what these working women in the film said: “We are not educated.” Even though I received a PhD degree, most knowledge I needed to become a woman was self-learned, to deal with various violence and power obstacles in life and work, if we don’t use the strategy of de-gendering. We don’t have power; we are the vulnerable group, in no matter what kind of society—democratic or authoritarian. We cannot simply enter an institution or power relation to play with the rules of the game as defined by the conventional and dominating power. We have to create women’s power out of our powerlessness.

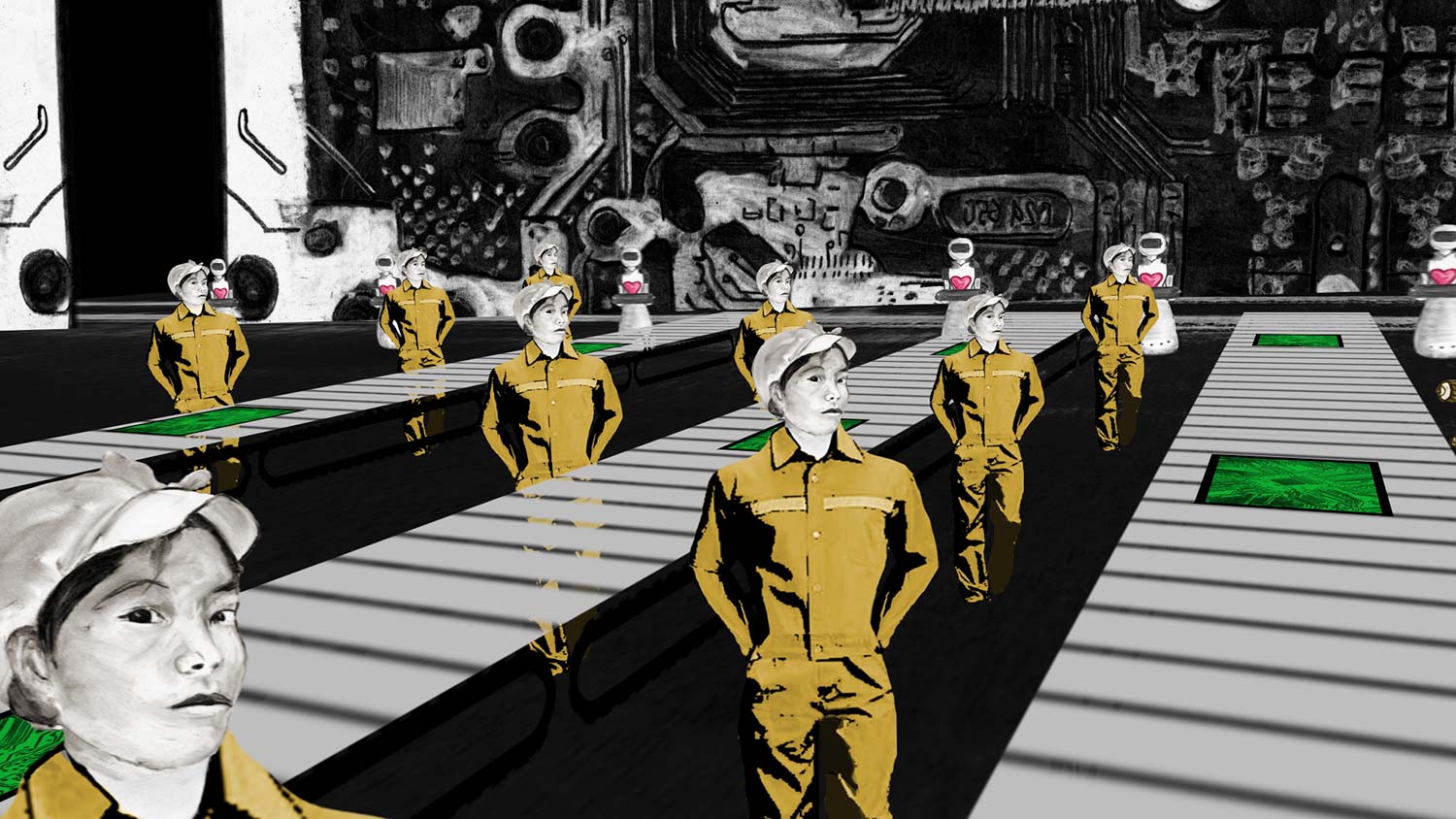

Outcry and Whisper is in dialogue with a previous film, We the Workers, produced by me and directed by Wen Hai in 2017. These two films capture the reality of workers’ collective actions in China—I do not use the word “social movement,” for in the Chinese context I doubt if there are conventional social movements. In both films, most labor action organizers are men, although in reality, most workers’ strikes were won by the collective of women workers. Due to the limited access to certain scenes for filming, we used footage shot by workers and labor activists themselves. When I searched for footage that put women at the center of the frame, I found very few. Thanks to Trish’s animation, we managed to represent women’s images and stories in a rich way.

Discussing the representation of workers, we can see the failure of organic intellectuals and public intellectuals in our society. Italian philosopher Antonio Gramsci stated that workers must produce their own organic intellectuals to speak for the working class. In China’s context, intellectuals, in the traditional sense, have a strong moral responsibility to serve the nation—namely, the government’s will in reality. Financially, Chinese intellectuals have to rely on either the state or the market for income. Sadly, for example, the documentary My Poetry (2015), which was allowed to be released in China, basically makes worker poets a spectacle, consumable, as they’re presented reading poems while ignoring the exploitation of what they documented in their poetry, not to mention the suicide of one of the protagonists, worker poet Xu Zhili. Even the New Left in China won’t publicly speak for the workers once they stand with the state. Not surprisingly, it is feminist activists who often stand with and speak for the workers. These worker activists in We the Workers and Outcry and Whisper, both men and women, both in speech and in action, are a special kind of intellectual; in Foucauldian terms, they are namely the grassroots intellectuals in China studies. They don’t talk in big words, but take actions in response to their own problems and specific social issues. They have to confront state power and capitalism at the same time.

However, when it comes to making a film about working women, we have far more challenges. It is first of all about idea conflicts among filmmakers and sponsors, due to implicit mansplaining while choosing footage, and the position women’s struggle holds in social action. In modern China’s history, the women’s movement serves to construct a “prosperous nation” or “democratic movement.” Nowadays, with the market economy in China, women are much more liberated than in Mao Zedong’s era, but also are restrained in frameworks of either contributing to the economic productivity and population reproduction, or being sexualized and commodified as desire objects in the market economy.

I am cautious about how power relationships are reproduced. I appreciate the beauty of human vulnerability. I am looking into the “person,” humanity, the use of reason, and solidarity. Through filmmaking, I want to create women’s framework, based on partnership and solidarity with nature and human society, for imagining a future for our society.

We went through many debates among filmmakers and sponsors during the filmmaking process. The essential question was whether Outcry and Whisper is to represent the working women’s story only—in the political space, the work space, and the intimate space, “struggling with their multiple roles: friend, lover, mother, worker, artist, boss, and more” (which was the two female filmmakers’ preference); or to see working women as only women working and striking in the factory (the sponsor’s preference); or to see working women’s struggle as an instrument or a process of a big unrest in China and Hong Kong against the authoritarian China’s political suppression (one male filmmaker’s preference).

You might see traces of these debates in Outcry and Whisper. We used footage shot by more than seven cameras, including mobile phones, and footage made with 3D animation. The relationship between people in front of the camera and behind the camera is different, and sometimes contradictory. This contrast in styles invites viewers to ask who is behind the camera, and what that means to the film and to the protagonist.

The other question is, In the editing room, how much power are we willing to share with our filmmaking team, our sponsors and our protagonists? How does the discomfort created in the editing room benefit the film and all film participants, without hurting anyone involved? I don’t have an answer; it really depends on the context.

For Outcry and Whisper, one of our sponsor’s guests said to our sponsors and filmmakers during the preview, “It is a film about women. If you don’t have a clear argument on the disagreements, just listen to women filmmakers’ voices.” Women should have the say!

China As Method: Gendering the Indie Film Community

Ironically, most prominent Chinese independent films do not get any chance to reach local audiences in China. Karin Chien’s dGenerate Films distributes a collection of Chinese independent films in the USA, including We the Workers and Outcry and Whisper.

Between 2001 and 2012, though censored or with little public visibility, there were de facto independent film festivals in China, held in a hotel room, in a private studio, on a bus, in a university, or in a private cinema. Since 2012, very few of these independent film festivals have managed to take place in physical spaces. Many filmmakers left China. Some went to Hong Kong and organized the Chinese Independent Documentary Lab. Of course, Hong Kong now is in a totally different situation under the National Security Law. Last year, we decided to close down the Chinese Independent Documentary Lab for various reasons.

The reality is, these independent filmmakers, who reside in Chinese language and Chinese culture whether they live in China or not, are in exile, having been marginalized in their home towns and in their host countries, dealing with loneliness and isolation in daily life, neither meeting their audiences nor “living” with their protagonists. Their creativity and thinking is trapped in the mode of ambiguities. I will say independent documentary filmmakers are indeed the grassroots intellectuals of our society; we are always, in the words of Edward Said, “as exile and marginal, as amateur, and as the author of a language that tries to speak truth to power,” whose method is “scouring alternative sources, exhuming buried documents, reviving forgotten (or abandoned) histories.”

The case of China has forced us and enabled us to find a way, a new journal, a new platform and a new paradigm.

What is crucial for the Chinese independent community is the ongoing circulation of an underground magazine named Film Auteur. Without regular independent film festivals, this magazine connects people, maintaining a loose network of independent filmmakers, critics and audiences. Though indie filmmaking is marginalized but avant-garde in our society, gender awareness is being even further marginalized. We have quite a lot of women filmmakers and independent documentary films about women.

However, many works about and by women have not yet received their deserved attention, discussion and distribution. We have to take our own action to create a feminist-friendly indie film community. With the emergence of young scholars, feminist and queer scholars, we are trying to make sex and gender and independent filmmaking issues gain more visibility in Chinese language in particular. A recent collection of ground-breaking scholar work is Feminist Approaches in Women’s First Person Documentaries from East Asia, published in Studies in Documentary Film this year.

I am also very excited to join the editorial team for Chinese Independent Cinema Observer, a new journal to be launched in Spring 2021, by Chinese Independent Film Archive, located in Newcastle University, UK. The reason I joined this journal’s editorial board is that more than half editorial members are feminist/queer scholars as well as filmmakers.

I hope my China story and feminist perspective will provide some inspiration for your future work.

Zeng Jinyan is currently a 2020 Post-doc Fellow at the University of Haifa. Zeng earned her PhD at the University of Hong Kong in 2017. Zeng produced and co-directed documentary films Prisoners in Freedom City (2007) with Hu Jia, and Outcry and Whisper (2020) with Wen Hai and Trish McAdam. Zeng wrote the script for the animation short A Poem to Liu Xia (Trish McAdam 2015), and produced the feature documentary film We The Workers (2017). Outcry and Whisper and We the Workers are both available for streaming on OVID.tv