In the opening moments of Petra Costa’s Apocalypse in the Tropics (2024), a short history of Brazil’s capital, Brasilia, representing the country’s hopes of modernity and progress, is immediately followed by a scene of evangelical members of Brazil’s Congress gathering in the main chamber of the National Assembly. Around a dozen members hold hands as they pray for the impeachment of then-President Dilma Rousseff and her “evil” government. The scene, filmed during the production of Costa’s previous documentary The Edge of Democracy (2019), becomes more than prophetic. Released globally on Netflix on July 14, Apocalypse in the Tropics traces the explosive growth of Christian nationalism that would help sweep Jair Bolsonaro to Brazil’s presidency and threaten the country’s democratic institutions.

Through voiceover, Costa argues that evangelical Christianity, which has grown from 5% of Brazil’s population four decades ago to more than 30% today, is a political force that has fundamentally reshaped Brazilian politics. The film (an IDA Enterprise grantee) follows the bombastic evangelical pastor Silas Malafaia through vérité sequences on his private jet, at home sipping coffee, and boasting how he has pressured former President Bolsonaro. The scenes reveal Malafaia’s role as a behind-the-scenes kingmaker who helped engineer Bolsonaro’s rise.

Costa’s narration weaves through these contemporary scenes with a voice that shifts between historical analysis, poetic reflection, and personal confession.

Different chapters in the film guide viewers through the theological roots of Christian nationalism (a throughline from 19th-century Ireland to Billy Graham and his historic visit to Brazil); Costa’s own earnest study of religious theory as someone raised without religion; and the suppression of liberation theology, a Catholic movement popular in Latin America that championed the poor, and its replacement with prosperity gospel messaging. Asked by Costa about why evangelical Christianity has experienced such tremendous growth in Brazil, current President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva offers the following story:

A worker loses his job and goes to the union. The union leader says, “Comrade, you need to get organized in the factory. Once we’re organized, we’ll have to go on a strike, and we’ll have to fight, and protest because of capitalism...”

The worker says, “I came here because I lost my job, and this guy wants me to start a revolution.”

So he leaves… and visits the Catholic Church… The priest says, “Yes, my son, you must suffer on earth to gain the Kingdom of Heaven. That’s life. Heaven belongs to the poor...”

The worker says, “I just came here to say I’m unemployed.”

Then the guy goes to Prosperity Theology church, where [the pastor] explains in two words: “The problem is the devil, and the solution is Jesus. It’s so simple. You’re unemployed because the devil has entered your life, but Jesus will fix it for you.”

And the guy is comforted because someone says he has a chance.

The competing visions of the evangelical promise of earthly favor for the faithful versus liberation theology’s call to aid the oppressed are made clear in the documentary’s most harrowing sequences, which document Brazil’s catastrophic response to COVID-19 under Bolsonaro’s leadership. Combining found footage and archival material with her narration, Costa shows how evangelical pastors simultaneously provided aid to desperate communities while spreading pandemic denialism, resulting in over 700,000 Brazilian dead.

Apocalypse in the Tropics builds toward the January 8, 2023, attack on Brazil’s federal government buildings in Brasília by a mob of Bolsonaro supporters—a scene that will feel strikingly familiar to U.S. viewers who witnessed and experienced similar scenes at the U.S. Capitol two years earlier. Further cementing these parallels are President Trump’s summer 2025 announcements of 50% tariffs on all Brazilian imports, partly in response to what he sees as a “witch hunt” against his political ally Bolsonaro, who currently faces criminal charges for allegedly plotting a coup after losing the 2022 presidential election.

As with Costa’s Oscar-nominated The Edge of Democracy (which broke viewership records on Netflix Brazil), the film operates on both intimate and epic political scales, examining how an anti-democratic far right reshapes individual lives and national destinies. A day after Trump’s tariff announcement, I spoke with Costa about the theological underpinnings of authoritarianism, the global reach of American evangelical influence, and why she believes “courage is demanded from us” in defending democratic institutions. This interview has been edited.

President Jair Bolsonaro, running for reelection, during a live interview at the headquarters of SBT television. Image credit: Francisco Proner. All stills courtesy of Netflix

An evangelical revival meeting.

A smashed window in Brasília on January 8, 2023. Image credit: Busca Vida Filmes

DOCUMENTARY: What is the connecting thread between The Edge of Democracy and Apocalypse in the Tropics?

PETRA COSTA: Brazilian democracy and I have almost the same age, and I thought that in our 30s, we would be standing on solid ground. Not only was I mistaken and a huge crisis in Brazilian democracy began at that moment, but that crisis has just intensified in the years after with the election of Bolsonaro [in 2018] and with the rise of a theology that we’ve been investigating, which is called dominion theology, that wants to basically take over the three branches of government.

During the filming of The Edge of Democracy, I filmed Pastor Silas Malafaia performing what he calls a prophetic act in front of the National Congress. One prophecy in this act was that God would take over the three branches of government.

I had promised myself that I would not make a sequel about Bolsonaro’s government because it’s really exhausting for the soul. But in 2020, when the pandemic began, I could not help but film that moment. I think it was the most tragic moment in our history that I have witnessed, where 700,000 people died. Half of those deaths were completely avoidable. What became evident was the omnipresence of evangelical pastors. They were giving assistance to people, like physical medical assistance and spiritual help in this moment of despair. But some pastors were also really going into a denialist speech, keeping their churches open, saying that Jesus would cure COVID. Many of them were inspired by that same pastor I had filmed in front of Congress, Silas Malafaia.

D: In that section of your film, during the early stages of the pandemic, in response to concerns about COVID, President Bolsonaro says, “Well, we’re all going to die.” It immediately brought to mind how U.S. Republican Senator Joni Ernst, a member of an evangelical church, recently responded to constituent concerns about Medicaid cuts. She said, “Well, we all are going to die.”

PC: This is why I wanted to make this film, because I wanted to understand how Christians can back a president who shows such little regard for human life. And what the investigation of this film took me to was the Book of Revelation, the foundational book for Christian fundamentalism, specifically a reading of it by a 19th-century Irish pastor, John Nelson Darby. Before Darby, many Christians believed that they had to create peace on earth for Jesus to return. Darby shifted that reading and said, “No, the world is going towards chaos and doom. And Jesus will arrive the faster the apocalypse arrives.” That created an apocalyptic thought that really spread through America after the Civil War, specifically in the South, and would then go to Brazil and shape our politics.

In this vision, Christ is not that compassionate savior of love thy neighbor, but he’s actually coming down to the earth as a general who will banish all the nonbelievers to hell and send the true believers to this dome in the sky. That thought has coalesced with a far right that also believes the weak should perish and the strong should survive.

And that’s the fatal marriage that we’re witnessing.

D: What about liberation theology as a countervailing force to the Christian nationalist right? There is a section about it in the film.

PC: The film has three layers. One of the layers is Brazilian politics and this marriage of religion and politics as it played out in the last four years in Brazil. Another layer is why did it come, and what is the theological thought behind it? And inside that layer is the genesis of how it came from the United States to Brazil. And that’s completely tied to the story of liberation theology and how liberation theology was spreading in the ’60s through Latin America. Liberation theology is very tied to several progressive movements, Leftist movements. In Brazil, it’s very tied to the origin of the Workers’ Party. Lula himself was friends with many liberation theology priests. Their vision was of a Jesus that is there to help liberate the oppressed from inequality, from the horrible conditions of life, which is the case in Brazil until today.

When we investigated, we found that both Kissinger and Nixon stated that liberation theology was a threat to American interests in Latin America. The Pope even silenced many liberation theology priests. The movement kind of died, but then these counter-movements surged. Most people say these are just conspiracy theories, but this is a discovery from our investigative journalist, Nicolás Iglesias from Uruguay. Working with us, he found these unreported documents showing that “the fellowship,” also known as “the family” [a conservative Christianity that wields influence in Washington], was sending missionaries to the Brazilian Congress to evangelize. And there’s that trip of Billy Graham to Brazil in 1974 that, by the order of the military dictatorship, was shown on all TV channels.

That’s one of the reasons why you see a surge in evangelicals. Some call it the fastest religious shift in history outside of wars and revolutions.

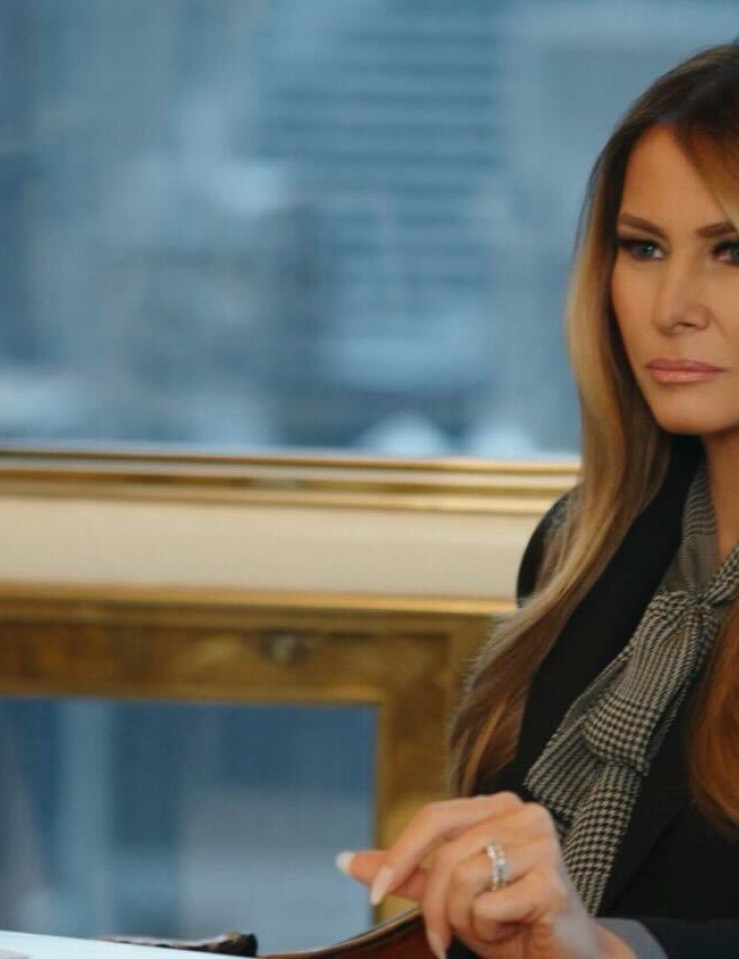

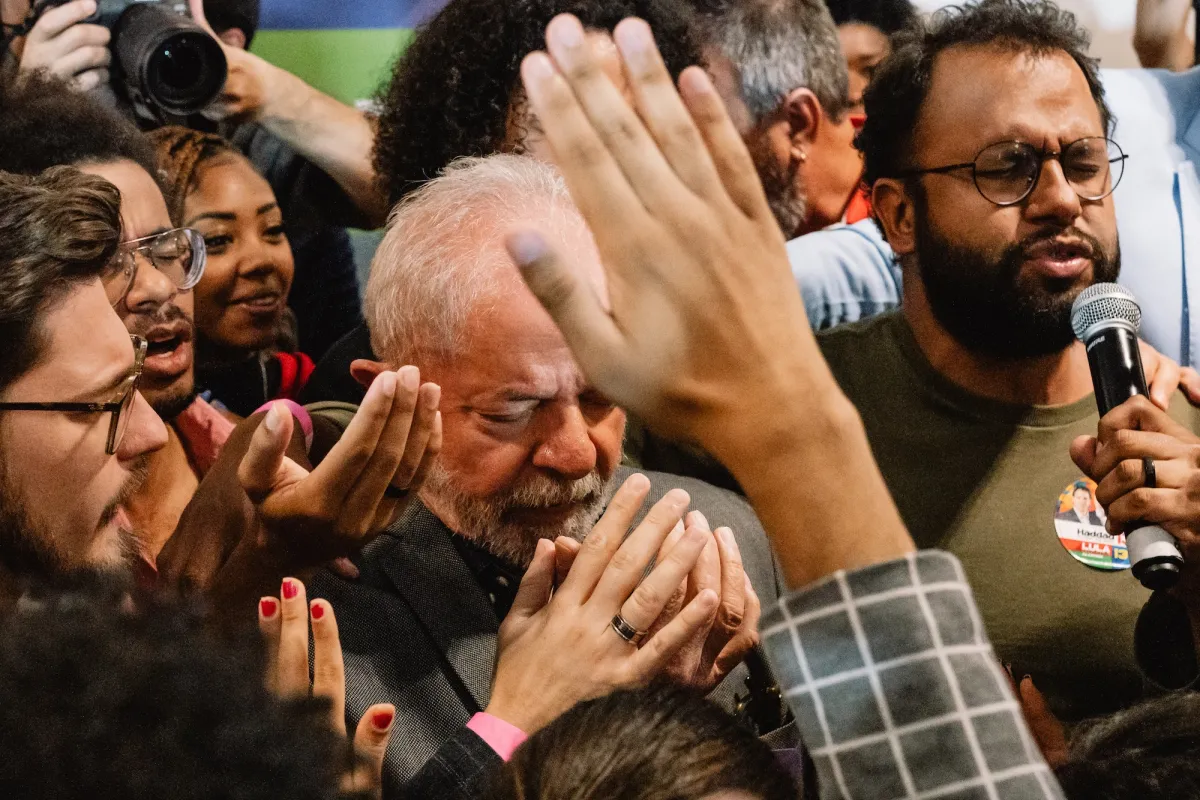

Presidential candidate Luis Ignácio Lula da Silva at a campaign event with evangelical Christian supporters. Image credit: Francisco Proner

D: In terms of the vérité material, why does someone like Malafaia want to participate?

PC: Malafaia speaks often to the press and to all kinds of press. I think he sees himself as an evangelist who has to spread his gospel, whatever form it takes, and for that reason he was happy to give us access throughout this entire time. It was harder to get access to Lula, even though Lula appeared in The Edge of Democracy. Our intention was also to accompany Lula during this time, but that proved impossible. It took us a year and a half to get one interview.

D: The film shows Lula going from saying he doesn’t want to “campaign in the church” to being prayed over by evangelicals, including a child pastor. How critical was that support to his election win?

PC: All the polls show that that support was critical, and that if he didn’t do that gesture he would probably have lost. Though it didn’t change that much because in the end, 70% of evangelicals voted for Bolsonaro. That’s more than any other segment if you include race, gender, class. Evangelicals continue to disapprove of Lula’s government because prominent evangelical leaders in Brazil continue to be very aligned with the far right, as no other president gave them so much access to power as Bolsonaro has.

D: On the one hand, this is a political story with global implications. I’m thinking of [Argentine President] Javier Milei, President Trump, and Elon Musk, for example. But you also have a very specific POV and a reflective or meditative approach to the story.

PC: Yes, my films were very personal. My first film, Elena (2012), is about the death of my sister and my coming to terms with that grief, that pain of losing a sister, and the trauma. My second film, Olmo and the Seagull (2014), is about the confusion of becoming a mother, even though I wasn’t a mother when I made it. You can think of my most recent films as films about how you lose your own identity and how to come to terms with that.

Both The Edge of Democracy and Apocalypse in the Tropics are about losing democracy and the pain of losing your own democracy. I saw many people around the world expressing that feeling. I am thinking of a British author called Tom Whyman expressing his pain of living through Brexit, a citizen who thought democracy was their birthright, who thought the future would be one where we would have more, and suddenly we’re entering a rabbit hole that is taking us back. Not only to times of fascism as we as humanity lived in the 1920s, but to the Middle Ages—presidents are trying to become divine rulers and pushing our countries towards theocracy.

D: Are there lessons that we can draw from the recent experience of Brazil?

PC: The main lesson is do not capitulate. It is leaning into fear and not backing away from it that has led humanity to bend towards justice. It’s in these times that the most courage is demanded from us, even if we’re going to be called traitors of the nation, even if they will call for prison. The more we capitulate, the faster they will manage to really execute what they want, which is censorship.

This piece was first published in Documentary’s Fall 2025 issue.