David Osit has built his filmography by asking uncomfortable questions about the stories we tell ourselves about progress. As a director-cinematographer-editor, Osit has consistently turned his lens toward subjects that resist easy moral categorization. His 2020 feature Mayor (supported by an IDA Enterprise grant) followed Musa Hadid, the Christian mayor of Ramallah, as he navigated the absurdities of governing under Israeli occupation—a film that found dark comedy in bureaucratic dysfunction while highlighting the human cost of political subjugation. Earlier, Thank You for Playing (2015, directed, produced, and edited by Osit and Malika Zouhali-Worrall), he chronicled a family’s decision to create a hit indie video game about their dying child, exploring how digital media mediates our most profound experiences of grief.

But Osit’s editing resume also includes work that directly connects his livelihood to the very phenomena his newest feature, Predators (2025), critiques. As one of the editors on HBO’s series The Vow (2020), he helped craft one of the streaming era’s most successful cult documentaries, turning the NXIVM scandal into television that attracted millions of viewers hungry for true crime content. His editing work on Hostages (2022, which won the IDA’s award for Best Limited Series) further ensconced him within true crime media production, even as that series approached its subject of international kidnapping with more nuance than typical genre entries.

Predators emerges at the intersection of two dominant trends in different sectors of contemporary nonfiction: the explosion of true crime content and the rise of personal documentaries that prioritize the filmmaker’s own story and self-revelation. Here, Osit deliberately commingles the two. One effect is that Predators examines his own complicity and that of his peers in the documentary entanglement of exploitation and entertainment. Predators is not the first—this trend has been noted by film critics in the rise of “prestige true crime”—but it is a uniquely fine-tuned and insightful example.

The film takes as its starting point To Catch a Predator, the Dateline NBC series that ran from 2004 to 2007, hosted by Chris Hansen. The show’s format involved adult decoys posing as minors in online chat rooms to lure potential predators to staged meetings, where Hansen would confront them on camera before the arrival of local police. The series became a cultural phenomenon in the U.S., spawning countless imitators and expanding the ethical borders of mainstream entertainment.

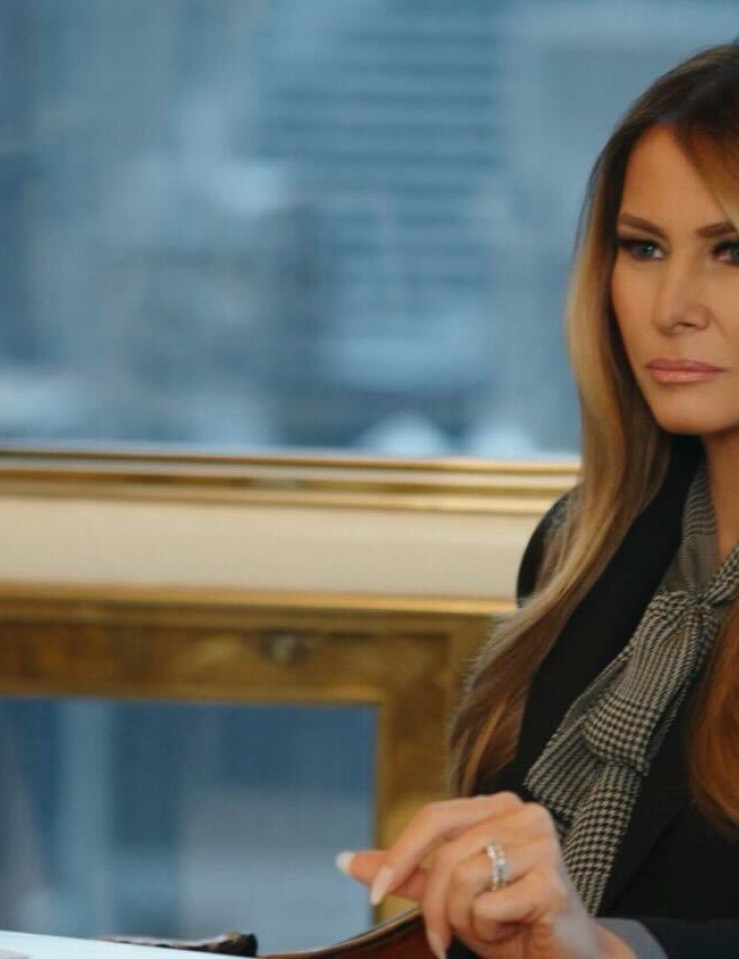

The film begins by examining Hansen’s journalism and the show’s influence, combining raw footage from To Catch a Predator with polished talking heads of police chiefs, an academic who provides a sociological reading, and two former decoys. Their testimonies reveal the psychological toll of participating in vigilante justice, including the show’s final case, where the suspect died by suicide after being exposed. Next, Predators follows, in observational style, current YouTuber Skeet Hansen, who has named himself after Chris Hansen and extended his confrontational style for internet videos. In the final act, Chris Hansen is given a chance to directly respond through a pivotal sit-down interview. Throughout the chapter structure, the documentary’s form fractures. What starts as recognizable reportage evolves into something more experimental and personal.

Central to the film’s compelling appraisal is Osit’s recognition that documentary filmmaking—including his own intimate portraiture and for-hire work—exists on a spectrum with true crime docutainment. Both practices involve pointing cameras at vulnerable people, promise to reveal hidden truths, and depend on the audience’s appetite for watching human struggle.

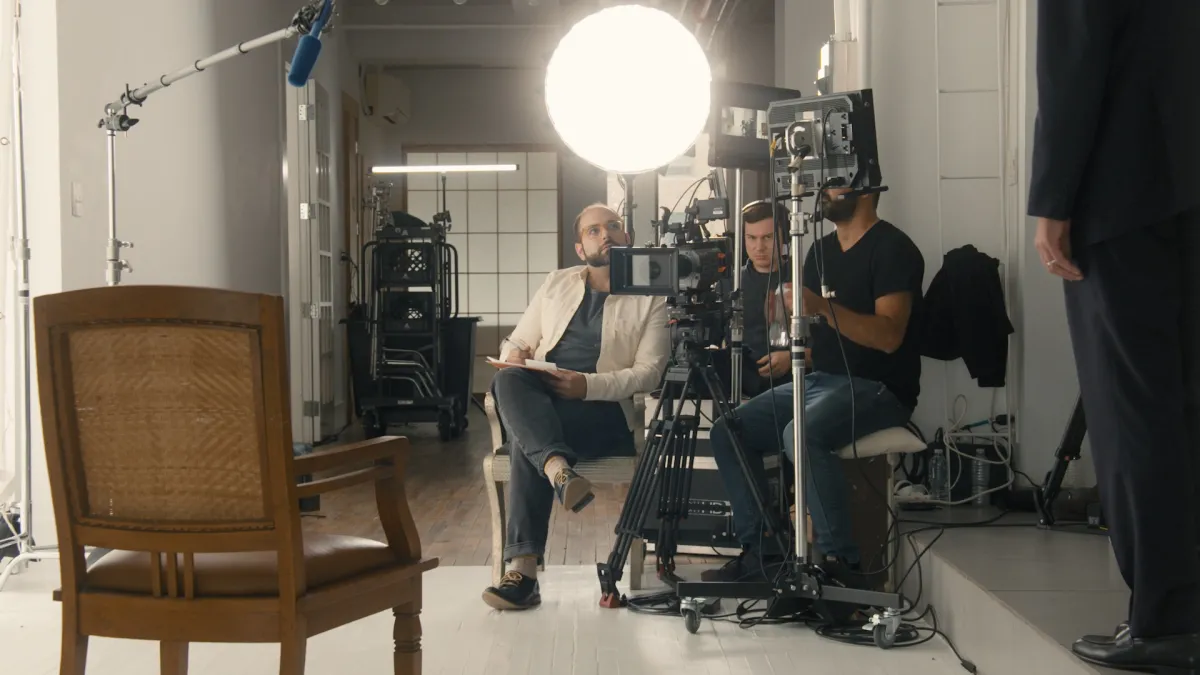

Predators’ final moments crystallize this central argument about complicity and choice. After examining TruBlu Entertainment’s corporate machinery for ruthlessly packaging Chris Hansen’s current To Catch a Predator spinoff and other true crime content, Predators concludes by following Chris Hansen as he awkwardly exits the interview’s film stage and walks out the door—exercising the very choice his sting operations denied the men he caught. But the film then cuts back inside the studio to rest on Osit’s own face, surrounded by his film crew, teetering between confession and reckoning. It’s a moment that refuses easy absolution and risks aesthetic posturing.

Acquired by MTV Documentary Films, Predators receives a limited theatrical release in New York and Los Angeles this month before expanding in October. In the following interview, Osit discusses the ethical challenges of making a film that critiques the medium in which it operates, the metatextual editing that serves his thematic investigation, and his enduring belief in documentary cinema’s power. This interview has been edited, and expands Documentary’s previous interview with Osit.

DOCUMENTARY: You spend the entire film making this argument that society is a little bit sick for liking the undercover sting shows and true crime documentaries. Into the continuum of Chris Hansen and Skeet Hansen, you also place yourself as a documentary filmmaker. How much are documentary filmmakers the aggressor or predator in our pursuit of stories?

DAVID OSIT: I think it’s disingenuous to suggest that documentary filmmakers aren’t part of the primordial ooze of finding stories and sharing them to advance certain ideas or mythologies. I believe that I’m doing good. I think most of us believe that we’re doing good work for a living—that’s true of everyone, really.

There are differences between me and Chris Hansen, Skeet Hansen, Joseph Pulitzer, and the yellow journalists at the turn of the 20th century, and there are similarities. Chris and I both make a living doing what we do. We are both incentivized to make what we do appealing to audiences. We also both feel confident that our opinion is one that we want to share and amplify. It’s not a judgment on other people. It’s just a basic fact of life in the modern media landscape, where you are inside a capitalist fight for eyeballs.

D: In the same way that there’s no ethical consumption under capitalism, there’s no ethical production either?

DO: I can’t really see how, if I am producing something in the context of it being bought and sold, that it could be ethical. It doesn’t mean that we can’t be good. We can care about what happens to the people around us, and we can have a code of conduct for how we operate.

There are certain rules that I would never intentionally break. I would never want someone to be harmed by a film that I’ve made. That feels like a line that I wouldn’t want to cross, and it’s one of the reasons why filming with some of the predator hunters in my film made me feel uncomfortable and call into question where I actually stood in terms of my moral ground.

D: During the Skeet Hansen sting, we see you start filming while hidden in the bathroom of a motel room, and you come out when a man is caught and reveal yourself as filming. Later in that same scene, there’s also a second reveal, when one of the producers of Predators, Jamie Gonçalves, also comes out of the bathroom and very gently explains to this man that the two of you are not part of the sting. Jamie presents this man with the choice to sign a release form—to decide to show his face or not, in your film.

DO: This particular moment wouldn’t have been a scene I included if it wasn’t standing in contrast to the people that I was filming, who were also making their own documentary, who weren’t asking for consent.

As the film proceeds, it becomes increasingly personal, not just for me but for the human beings involved in these productions. In that moment, I really experienced what young people call cringe, which is that you see yourself through the eyes of somebody else, and you don’t like what you see. I don’t know who that man is; I don’t know his name. As far as I was concerned, in that moment through his eyes, there was no difference between me and Skeet. We were the same. We both had cameras pointed at him, and I felt this need to try to say that there was some sort of difference between us.

D: How did you cast Skeet Hansen? In this popular subgenre of internet crime sting videos, why was Skeet chosen as the representative?

DO: Quite simply, I cast Skeet because he’s the scion of Chris Hansen. He named himself after Chris Hansen, imitates him, and uses the folklore of To Catch a Predator as part of his routine. There are other predator hunters who don’t directly mimic Chris Hansen. But once I started filming with Skeet, I felt like I had gotten what I needed.

D: Another distinction we can draw is between an unscripted show’s host and a first-person perspective in a personal documentary. Near the end of Predators, you disclose your own personal connection to this type of material. Internationally, within the documentary industry right now, there is a lot of focus on making sure filmmakers are proximate to the subject matter, authentic in their voices, and representative of the community being filmed, which correlates to a rise in personal documentaries. This conversation isn’t reflected in general audience concerns. Do you think the personal aspect makes your film stronger, and why did you decide to include it?

DO: I’m not sure how much I want to talk about my personal connection for people to read before they see the film. I feel like it’s important to preserve how people come to that organically in the film.

There’s this explosion of true crime designed to propagate entertainment through nonfiction stories, and that’s really not what I fell in love with when I first got into documentary filmmaking in the early 2000s, at the dawn of the DV revolution. These films get made by anonymous filmmakers for anonymous reasons. There’s no motivating factor behind some of the nonfiction series on the major streaming networks except that they are profitable. We all understand people watch crappy TV; we all accept that.

And then there are documentaries that are designed to use all the catchphrases of “shine a light onto societal ills” and “hold a mirror up to our society.” I’m not trying to say that one is valuable and the other is not. But between the two, one of those types of documentary films is allowed to become personal, and one is actively discouraged from being anything but a commodity. I wanted to make a film that maybe jumped between the two, and to see what that did to an audience. In many ways, this film was trying to make a radical act of messing with your expectations.

D: Are you trying to Trojan horse your way into an audience that might actually just want to watch a recap of To Catch a Predator?

DO: After I made Mayor, I got some emails and calls about true crime ideas, and I just wasn’t terribly interested in a lot of these approaches. And then I was like, “Why don’t I make a film about how much true crime bothers me?” That’s where Predators came from.

Ever since I started making Predators, this phrase you just used, “Trojan horse,” has become some sort of magic phrase that every network uses about what kind of true crime entertainment they want to make: “We really want to find a film that can be a Trojan horse and start as one thing and become something else.”

I do wish more documentaries came with thought bubbles above them: Why does this exist? Why did the filmmaker want to make this? What’s interesting about it to them?

I’ve never felt to this degree the way in which our world seems to be informed by how entertained we are. The people that I interact with will get their news from the most entertaining source, not the best source. And I think that the line really started to become blurry from shows like To Catch a Predator—when entertainment became an outcropping of something that purported to be journalism.

D: You specifically address how journalism can shift in the structure of Predators. I’m referring to how the edit starts from a very straight broadcast journalism approach and later incorporates more vérité, plus a staged interview with Chris Hansen. You conducted an interesting exercise where you split the film into four parts and gave each to a different editor—Erin Casper, Robert Greene, Charlie Shackleton, and Nicolás Staffolani. It seems that the final film still keeps a lot of this form. What did you learn from this exercise?

DO: I intrinsically understood that the way the film would work is if you, as an audience, could feel like you were on the journey with me. The thing that first compelled me was watching footage from To Catch a Predator and feeling this discord between the edited show, which has a dark comedy and reportage, and the raw footage, which is at times devastating, humanistic, and horrifying all at once. I knew that I couldn’t give you that experience without showing you both. Sometimes, the experience would have to mirror the experience I had watching all this raw footage—the same experience that any editor has when they’re sitting and watching rushes and they’re like, “What am I looking at? I can’t believe this.”

I gave certain chunks of footage to certain editors and didn’t tell them what the others were working on. For example, the first thing that ever got edited was a big chunk of the middle of the film, which is entirely archival footage, that I gave to Erin Casper. I said, “Make me a 20-minute true crime movie out of this. Cut it as though you would be watching any sort of true crime film.” What I got back was completely different tonally from what the rest of the film would be, but that’s what I liked about it. It helped me access a different rhythm of what the story could look and feel like.

The throughline ended up being me as the director and acting more like a supervising editor, hearing ideas from these four brilliant editors, who are all extraordinarily different from one another in their sensibilities but all with good taste and good passion.

Robert Greene, coming from this vein of films that are really about the construction of a film and the mise en scène that goes into filmmaking [Procession, 2021; Kate Plays Christine, 2016]; Charlie Shackleton, having simultaneously been embroiled in his own true crime pastiche [Zodiac Killer Project, 2025]; Erin Casper, a brilliant editor [Fire of Love, 2022] who I just knew would be able to have an ability to make a true crime thing, which was the last thing I wanted to try to do on my own; and Nicolás Staffolani, a filmmaker [and editor of Cold Case Hammarskjöld, 2019] based in Copenhagen, who was able to look at the nuances of this show with fresh eyes and not see it as something American, but something truly alien. Having those four voices was vital for me because I couldn’t be on my own for this one.

D: This film is bigger than any of the other films that you’ve directed. You also worked with a team of producers, other cinematographers, and camera assistants on various shoots. What did this increased scale bring to this production?

DO: My next film is back to the way I made Mayor. It’ll be me, and I’m sure I’ll show cuts to a couple of friends down the road again.

Predators has to feel like a true crime movie, or else the illusion won’t work. So I genuinely just felt that I had to cosplay as a true crime film director. I guess that means I need to have a bigger team, have a DP shooting it instead of me, or rent lights.

This idea of this film being about how all of us, all filmmakers, audiences, journalists, are all part of this cycle of hurt, whether we want to be or not? I couldn’t go on that journey unless I built the house correctly, and the house had to look right. I don’t think a film can change your mind, but I think it can change something deeper inside of you than your mind.

D: Your film addresses why shows like To Catch a Predator are bad at helping viewers think differently. But for the really, really hard questions, documentaries are also bad at addressing the why. They don’t quite seem to be living up to the current moment. There are more documentaries being made than ever, and suffering persists. What exactly is the utility of the feature-length documentary form to you?

DO: Imagine if you swapped out the word documentary for art. What is the utility of art? What I mean is, what’s the utility of asking questions of the world we live in, of deciding that we’re not necessarily happy with how we treat each other, or questioning the idea that there’s not one moral stance about what is good and evil or right and wrong?

This film came from a deep place of disaffection with what the commodification of media has done. But it also comes from feeling a deep sadness at our society’s inability to find empathy for people and desire to shun those who try to. Nothing is more indefensible than being a child predator. It’s not about whether we care about what happens to these people. How do we live in a society that can find a way to make someone into an evil entity? We’re doing that on massive scales all the time. There’s a genocide happening. We’re in a situation where all it takes is the side with power to be able to construct an identity of the people being killed and say that it’s justified.

I have to believe that we would be a better society if we saw people with nuance, and I think our media would be better if it did the same. I want to make more films that do that. The utility is that I’m just trying to make the world I believe in.

This piece was first published in Documentary’s Fall 2025 issue.