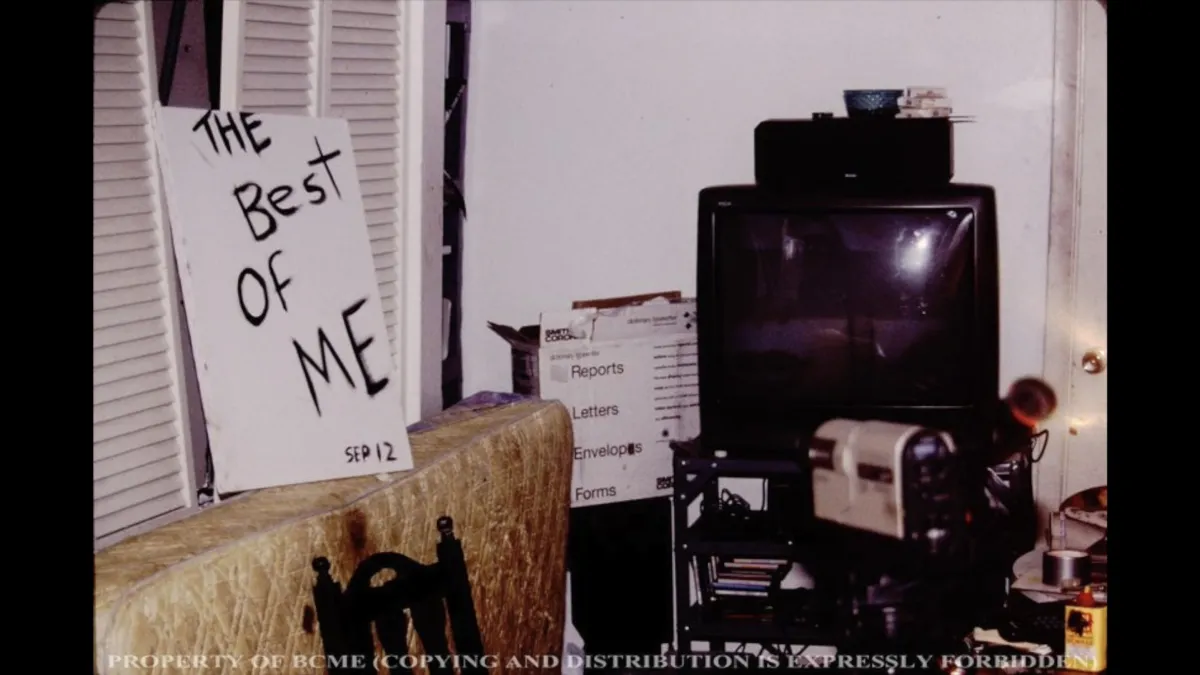

“He’s Kind of the Original Vlogger”: In ‘The Best of Me,’ Heather Landsman Traces Ricardo López’s Violent Obsession with Björk

By Alex Lei

Courtesy of Heather Landsman

On January 14th,1996—his 21st birthday—Ricardo López started videotaping himself laying out his plot to attack the Icelandic popstar Björk. In this initial tape, López said Björk was a symbol of purity and innocence to him, an image which he said she destroyed by having relationships with two different black musicians, previously with Massive Attack’s Tricky and, at the time of his recordings, English music producer Goldie. López lays out his initial plan to send Björk a package that would infect her with AIDS. As the tapes progressed, he changed this plan to a letter bomb containing sulfuric acid. The final tape, in which López commits suicide wearing red and green zigzagging face paint while Björk’s music plays in the background, now has a notorious reputation on the internet, with gifs of it being linked by online trolls or the clip being edited into other videos for unsuspecting viewers.

Filmmaker Heather Landsman seriously considers López’s footage in her new film The Best of Me, which condenses the 20-some hours of tapes López produced into a hauntingly candid look into a deeply unwell and alienated individual. With The Best of Me, Landsman strives to create as objective a viewpoint on López as possible, offering no direct commentary of her own, instead letting López reveal—often in duration—his terrifying and sad psychosis. The footage that Landsman assembles feels incredibly prescient: in its proto-vlog format, its engagement with a life that has been reduced to a memetic “creepy pasta” image by the internet, and its explication of an extraordinarily lonely individual’s violent fixations built from media consumption.

The Best of Me is being independently distributed by Landsman through the Film-Makers’ Cooperative, touring microcinemas. Upcoming screenings include Los Angeles’s Whammy! on May 9 and the Cooperative itself in New York City on May 24. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

DOCUMENTARY: The Best of Me reminded me of the feeling of stumbling across these videos in the middle of the night and sitting with them for a long time, condensed to 90 minutes. Is that what you were going for?

HEATHER LANDSMAN: I think my first exposure to this story was stumbling upon it as a kid when I shouldn’t have been, and it freaked me out. One thing I found interesting about this is how it got mythologized on the internet, especially the final tapes with him in that red and green face paint. That image really stuck with me. I definitely knew from the get-go that I wanted it to be no editorializing, no commentary—just straight from his words. Naturally, that structure came with it, especially even in regards to the proto-vlog style. I didn’t think about it a lot as I was editing it, but it’s one thing that a lot of people have brought up to me since: he’s kind of the original vlogger. He used this style of video diaries to talk to himself or the camera in the mid-to-late 90s, before it became such a normal part of YouTube and the internet.

D: His candidness is shocking. It’s almost as if the camera is just a way to speak to somebody, but it also puts the viewer in a therapist's perspective.

HL: The idea of adding any kind of commentary to it felt wrong to me because you get all of it from him. He incriminates himself in every facet and any possible way that people could diagnose this case. Something that was very important to me was that I wanted this to be a very objective viewing experience because, really, he says it all. There’s not anything that’s super vague. He just spills it all.

D: And he does it right off the bat. The first thing he does when he starts recording himself is admit that he has this racist psychosexual fixation on Björk and the fact that she is with a black man is why he feels he has to punish her. He doesn’t leave anything up for interpretation, he’s been thinking through it the entire time.

HL: Before really editing it, I looked back at this one documentary that was made right in the midst of this case happening, The Video Diary of Ricardo López (1999). It’s not very good. You barely get any of his voice, it’s just someone narrating over little snippets of the footage. You can’t talk about the case without talking about his racism. The way I want the viewer to sit with this person, I want it to be in this very grounded, empathetic sense and not gloss over any of those monstrosities. Watching through the footage, it hits like a bullet—the language he uses, the way he talks about her and her boyfriend at the time, and also himself.

You get this very interesting window into his life surrounding his plan, but also a little bit of what his life is outside of that and his mental state at the time.

D: He’s very open about how this fixation is entirely formed by his media consumption and how insular his life is—he’s open about being a virgin, and he self-diagnoses with Klinefelter syndrome, too. We get glimpses of, “Oh, his parents are calling and they’re concerned,” or he talks a little bit about his job. That’s an entirely different world than what we see, we see just what’s going on in his mind in his apartment.

HL: One of the most impactful tapes is that one where he talks about his condition and also his family life. Though he mentions his mother throughout all the tapes, he starts talking about his mother, about how “My mother will be emotionally destroyed because of this.” I knew that whole tape was super essential to include because of that. Like you said, it’s that brief window into his life outside his plan.

He also, in that tape, mentions Michael Mann’s Heat (1995). Watching through all the footage, there would be points where I would lull back listening to what he was saying and what kind of visual information was in this tape. All of a sudden I heard that quote and was like “Wait, what?” I had to run that back and include that.

D: That part is funny too because he’s trying to remember the quote while he’s saying it, and says it a couple different ways. But he really wants to get out exactly what it was, and he wants to be recorded the exact way he wants to be seen. He’s thinking about how somebody would watch and interpret him the whole time.

HL: It was very important to me to include the outside the edges of that—setting up the camera, flubbing his lines (if that’s what you want to call it), fixing his setup, things like that. I knew that needed to be in there to give you a little bit of a sense of him when he doesn’t think the camera is rolling, or footage that he doesn’t think people are watching.

D: By allowing the film to speak for itself and be self-evident, it lends a certain “objectivity” compared to documentaries where the filmmakers choose to use archival footage to editorialize, like Grizzly Man (2005), for instance.

HL: One inspiration for me—both as a formal aesthetic but also as thematic and ethical reference point—was Gus Van Sant’s Elephant (2003). It’s one of my favorite movies of all-time. While The Best of Me is a documentary, a lot of people forget that in making a documentary you narrativize real life, in every interview for Elephant in the press run, Gus Van Sant talked about how he didn’t want to diagnose the shooters. The role of the form of going between these different perspectives and following them unbroken was to give you a sense of every single thing leading up to it and you take that as you will. It doesn’t pinpoint one specific thing, it shows everything.

When making The Best of Me, I knew that this needed to show every single aspect of his life that he brings up in reference to Björk. At the same time, reading through writing on it and also the way it got mythologized as this piece of visual internet horror or “creepy pasta” troll gif, it really struck me how little any of the real coverage of it or online actually got into just his life and his mental state at the time.

D: In the 2010s into the post-COVID moment, online incel culture became very endemic in young men. Was this something that was on your mind while going through the footage?

HL: I wasn’t really thinking about it while making, but having seen the movie at the different screenings and just sitting with it and thinking more about that kind of rise in that weird corner of the internet that has that fascination with “lolcows.” Ricardo López predated that, but there is a throughline to it. Something that always really disturbed me is men on the internet’s fascination with these sad people who are clearly hurting. They are clearly monstrous in many ways, but also they clearly need some form of help. There’s been such a weird rise in it, especially as of late with stuff like Chris Chan and Daniel Larson. World of T-Shirts is someone who’s less of a monstrous person but clearly hurting. They all got lumped together into this modern niche of people who have become a punching bag—in some ways, rightfully so—but treated as a joke.

Alex Lei is a writer and filmmaker based in Baltimore. His writing on film has appeared in Documentary, Filmmaker, and Paste magazine, amongst others.