Welcome to The Synthesis, a monthly column exploring the intersection of Artificial Intelligence and documentary practice. Co-authors shirin anlen and Kat Cizek will lay out ten (or so) key takeaways that synthesize the latest intelligence on synthetic media and AI tools—alongside their implications for nonfiction mediamaking. Balancing ethical, labor, and creative concerns, they will engage Documentary readers with interviews, analysis, and case studies. The Synthesis is part of an ongoing collaboration between the Co-Creation Studio at MIT’s Open Doc Lab and WITNESS.

Synthetic Sincerity, a creative documentary premiering at IDFA, follows a quixotic quest to reveal human character. The film purports to make parallels between AI and documentary practice, but it mostly relies on human-generated scripted fiction to do so. It’s a hybrid piece that roams untethered through fiction, nonfiction, and AI-generated characters (or are they?), unveiling in the process pseudo-scientific and problematic documentary methods behind its own production.

The setup is this: documentarian Marc Isaacs is hired by a (fictitious) AI lab to hand over his archives featuring tricky interviews with real documentary subjects he has filmed over the years. The footage is valuable to the “Synthetic Sincerity Lab” because, according to what Isaacs presents, the subjects are either lying or discussing cheating and stealing. Isaacs also films new material with a vulnerable documentary subject (a political refugee) and pretends to collect AI-type data about him with the scientists.

It’s an embedded narrative in which the scientists are researching whether a synthetic version of this (real) subject can better express his inner thoughts than he, as a real-life human, is too frightened to share out loud. Their task is to mine how lens-based and data-driven observations can bring us closer to human character with the goal of creating more authentic synthetic characters. Isaacs goes off script, though, as he wanders into his cast of characters’ “real lives” through documentary elements. The whole project eventually derails into a (fictitious) AI tech demo and a (fictitious) university oversight inquisition.

Ahead of the film’s premiere at IDFA, we caught up with Isaacs to pull back the curtain on the workings of his intentionally befuddling film. The following interview was edited for length and clarity.

DOCUMENTARY: Where did the idea for this film come from?

MARC ISAACS: Ideas run into each other from previous films. This is the third film that I’ve worked on together with a screenwriter, Adam Gantz. We’ve looked at questions of documentary construction and documentary truth, questions around performance and myth, and how lines of documentary and fiction merge. What’s happening to the image? More and more, we are watching people who don’t exist. What does this mean for documentary film? It’s like the death of representation. The death of the camera.

Adam told me about an AI lab at University of Surrey. That was [the foundation for] our fictitious invention. One of the first things we shot was me going to the lab and giving a talk to the people you see in the audience there, all of whom are PhD students at the real lab. We started to think about them as characters. The film developed from that situation.

One of our original ideas was that I’d had quite a bruising experience at a university where I teach. I was suspended for a year. Different kinds of accusations around racial stereotyping and stuff like that. It was all very Kafkaesque and very odd. In the end, I had a year off from the university where I was investigated. Nothing really happened. It was dismissed as a non-event. But I was thinking about a film set in a university. I would play a tutor who was working with a group of students. That would allow us to talk about what was happening in institutions, about what could be said and what can’t be said, and how things spiral out of control very quickly. The students would film people in my local area, one of whom would be the Uyghur chef, Ablikim Rahman, my neighbor. So he was floating around in early ideas, but ended up in this film in a completely different role as we moved away from that notion and developed this idea.

Ideas usually work like that for me. They’re from conversations or experiences that I’m having, and eventually crystallize.

We’ve looked at questions of documentary construction and documentary truth, questions around performance and myth, and how lines of documentary and fiction merge. What’s happening to the image? More and more, we are watching people who don’t exist. What does this mean for documentary film?

D: You’ve opted not to disclose what is fiction, nonfiction, what’s made by AI, and when you are pulling someone’s leg. In the context of AI, given the severity of the current existential and epistemological crises, can you talk about that creative choice?

MI: I’ve never really believed in the term “documentary.” Even in my more simple films, there are lots of things that I’m hiding from the audience. In other films of mine, I’ve let the audience in on the construction because it became part of the narrative of the film. There’s a kind of trust that one places in the documentary filmmaker. It was important for me not to say that they’re lying to us, but for us to question these things in the context of the world we’re living in.

In this film, you’re not sure whether this lab really exists. Do they really do that work? Are the people who work in the lab really AI workers?

It’s inviting the audience to think about what’s happening when we can watch images of people that don’t exist, and emotionally connect to them and believe in them. Maybe that’s where we’re heading, that we can laugh and cry at an AI character. Maybe it doesn’t matter. Maybe it can be used in a way that’s really artistic and brilliant, and we connect like we do in a great novel. I’m really interested in that. I’ve never made journalistic films, so I’m not coming from that background. It’s fiction. It’s documentary. It’s putting images and sounds together in interesting ways to provoke the audience to think about how we receive images.

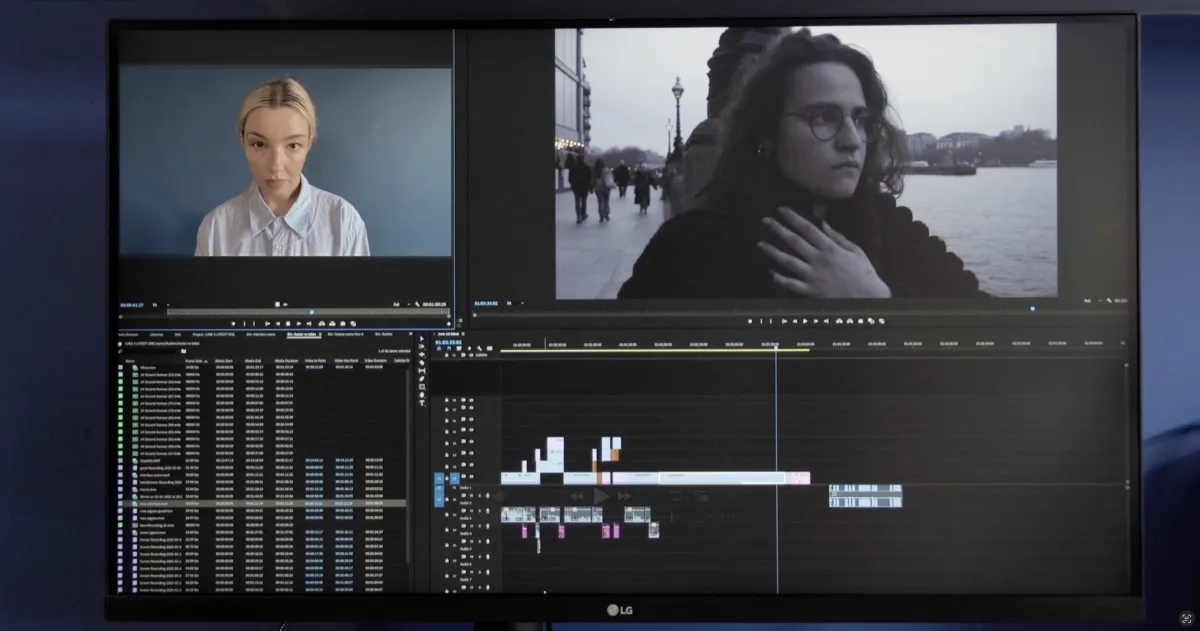

Ilinca Manolache, who plays the Avatar is a Romanian actress whom I filmed on Snapchat and then put her through an AI machine. It looks exactly like her, but it’s actually AI-created. And I’ve changed her accent so I could type in words for her. She’s kind of interesting in herself, because most actors and actresses would be horrified at the idea of them being made into AI. But she was really up for it. So all the time, it’s in that hybrid space.

The AI version of Ablikim Rahman, the Uyghur chef, is actually real footage made to look like AI. The irony is that AI is so perfect now that it looks a little bit too perfect; you can’t always tell the difference. Ours actually looks like AI from years ago, rather than contemporary AI

D: It’s all about context. These questions of the documentary project are not new: truth claims are problematic, our relationship and the trust in the documentary maker are complex. However, we are currently experiencing a significant context collapse. What do you feel audiences are left with?

MI: I remember when I studied cultural studies, one of the first things we learned was how to deconstruct a text: to think about its context, to think about who’s involved in the creation of the text in the first place. Is it a man? Is it a woman? Is it somebody from a particular ethnic group of relevance? Now more than ever, we need to be able to think about what we’re watching. I’m not in the business of trying to distort facts, but I am interested in provoking these questions.

D: You create sharp parallels between the way documentarians relate to their subjects and the way these AI labs interrogate and exploit the subjects’ likeness, data, in all territories, in perpetuity, in all forms of media. Can you talk more about this parallel that you’re drawing?

MI: These scientists don’t really work with human character in real life [the lab works on the question of AI-generated responses to real-time human line drawings], but we talked to them about the work they do with AI. Then Adam and I would come up with ideas of how they might talk about the people that I was bringing to them.

In the editing phase, I cheated some of my responses to some of the things that they were saying during the shoot. We realized this parallel of what they’re seeing and what I’m seeing. We were drawing out differences between the way that scientists would look at character, because I’m pretty sure AI will never be able to give weight and complexity to their characters. When you see synthetic characters, they don’t have the the gravity of a human. Most avatars that are made at the moment are for marketing purposes. People look very perfect and quite boring. Whereas if I walk down the street, I’m seeing faces that are showing the signs of a lived experience. I use the quote of Georg Simmel, about the aesthetics of the human face, of how experience remains on the person. It’s a moving idea, somehow, that your life experiences are written on your face, and that’s what leads to character.

D: What did you learn about your practice and the larger documentary project in this process of making this film?

MI: I don’t feel like I can simply go out into the world anymore and make films like I used to. People are so used to being filmed. There’s a level of awareness that people have about how they are in front of the camera that I don’t think you can ignore questions of performance. The learned behavior is reflective of the media culture we live in. That, for me, sometimes makes the possibility of documentary much less interesting. In the past, I felt I could go out and film and find moments that felt surprising and new and fresh. Now they feel like I see them all the time on YouTube. It’s forced me, over time, to bring something that is outside of the observation and the reality to a project, to keep it elevated.

D: Therein lies the promise of the synthetically derived image. It effectively erases the need for a camera and the problems that come with it. It promises to get “closer” to the subject using other means.

MI: It’s very sad to think about. The joy I get from going out with a camera to discover authentic things from real life, even if I then bring those images into another narrative frame or another method, it still seems important to get that from real life. To discover characters like the people working in that lab. But maybe it also feels important to mix it with something else, to give the material a form or a shape that can’t be found in reality.

I’m also really quite intrigued about these images that can be made without a camera, without me leaving my desk. What does that mean? I get very nervous about making a film where you don’t really connect with people.

D: Once everything is put into question, in the context of malicious actors on the internet, challenging the veracity of anything and everything, we’re left in the fog of war. If we just question everything to a point that there’s no reality, there’s no indexicality, then what are we left with?

MI: That also scares me. It’s also quite intriguing at the same time.

D: So, what do you think you’re leaving your audiences with?

MI: I think I’m leaving the audience with this kind of discussion that we’re having right now.